Roman Military Victory:

Scene on the Sarcophagus of Helena, Mother of Emperor Constantine,

4th c AD. Red Marble Porphyry. Vatican Museums, Rome

Roman Military Victory:

Scene on the Sarcophagus of Helena, Mother of Emperor Constantine,

4th c AD. Red Marble Porphyry. Vatican Museums, Rome

Rome on the Move

From Expansion to

Civil War

The Leaders

The Led

The Losers

Remembering War:

The Roman "Triumph"

|

|

Roman Warfare: The Leaders, The Led, The Losers

In the Vatican Museums in

Rome stands the marble sarcophagus of Helena, mother of the

Emperor Constantine. It's dense and red, almost glowing, as

if Roman domination from long ago is shouting out to

us.

The Romans are protected by metal helmets and body armor. Their

weapons are large and heavy. They

charge on fierce and frightening horses.

The defeated stand below the riders, some in chains. None exhibit

the horrific wounds common in ancient pitched battles. Nor

the signs of starvation or disease typical from siege warfare.

They are beaten down by something more powerful: Roman

relentlessness.

Notable Commanders:

King Numa Pompilius

Camillus

Marius

Sulla

Pompey

Julius_Caesar

Notable Losers:

The Etruscans

Pyrrhus

Hannibal

SOURCES

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ROME ON THE MOVE

The City of Rome was founded, in legend, around 750 BC.

For the next two hundred

years, it perched precariously among the

ferocious groups on the Italian peninsula. Still small,

still behind the Etruscans, rather a nothing.

Then, around 550 BC, Rome began to conquer and expand.

It kept fighting for the next 500 years.

Within

300 years, Rome had defeated everyone in Italy. The defeated

often became "allies," whose purpose was to provide units of

soldiers under the command of the Roman Army, and treasure

to support them.

By the time of Julius Caesar's death in 44 BC, the Mediterranean had become a "Roman

lake."

Roman armies with their perpetual manpower machine could

fight

east or west.

Spain was prized

for its metals and minerals, the southern Mediterranean/North Africa for its

granaries, and the East (the Middle East) for its rich cities.

The lands north of the Alps, the heart of today's

Europe, did not count for much.

|

|

Roman Empire

at the death of Julius Caesar, 44 BC.

Map courtesy

Ancient World Mapping Center.

|

|

|

|

|

|

FROM EXPANSION TO

CIVIL WAR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Julius Caesar was

assassinated in 44 BC. His murder restarted the civil wars

that Marius and Sulla had waged in the 80's. A generation

of Romans had since known peace, but the memories of the

earlier trauma remained. Perhaps the renewed strife appeared

as cyclical and thus inevitable. In Epode 16, Horace wrote

that his generation of Romans were "of cursed blood."

In his view, what even Hannibal could not accomplish--the

destruction of Rome-- Rome would.

This Civil War was

also a major event in Mediterranean history.

The Romans

had extended their domination beyond the Italian peninsula.

From Syria to Spain and in northern Europe, cities, towns,

and villages were affected by the Civil War's chaos and violence.

The Civil War was the "total war" of

the ancient world. Military participation from the

17-to-46 age group was high--about 25%-- meaning every Roman

family probably had at least one male in the War. Political purges carried out by

dreaded killing squads finished off many more. Mothers

and wives at all levels had many dead sons and husbands to

mourn.

The demands of the Civil War changed some of Rome's most

bedrock social institutions. Women were taxed, unheard of and undermining the sacredness of the

marriage contract. The place of the Army in society changed:

no longer was it unusual to see an Army inside the pomerium,

the sacred boundary, of Rome.

Property of Romans, including entire towns, was

expropriated. Often the lands were

later given to soldiers as a reward and lost forever to

their rightful and often innocent family.

Treasure from sacred temples were carted

off. Taxes everywhere increased.

Cicero wrote that it was a time when chance counted for more

than reason. Caesar's assassins won some battles and lost others.

Finally defeated by Marc Anthony, Octavian (Julius Caesar's

teen-aged adopted nephew), and others, the assassins left

the stage but the victors quickly declared

war on each other. Eventually just Marc Anthony-

Cleopatra were left to battle it out with Octavian. Octavian

won. Marc

Anthony and Cleopatra committed suicide.

Octavian went on to

become Emperor Augustus. Surprising to everyone considering

Octavian's extreme brutality during the Civil War, internal peace

descended on the Roman empire,

though at the price of autocratic rule, for the next 41

years.

As for Cicero, by chance or by reason, he had chosen the wrong side.

Proscribed, Marc Anthony's soldiers murdered him near one of

his country estates. Cicero's head and his writing hand were cut off and carted back to

Rome for display on the Rostra in the Roman Forum.

|

|

The Emperor Augustus.

Pinecone

Courtyard, Vatican Museums, Rome.

Horace in Epode 16: "A Remedy for Civil War" wrote:

"Another generation now's been ground down by civil war, and

Rome herself's being ruined by her own power..." Survivors carried the memory of the

uncertain, violent times for decades.

|

|

|

|

|

THE LEADERS

The Art of Generalship

What did Rome expect of a military leader?

Political deftness: To obtain a command, a Roman male had to

get to the top of the political heap. The head Commanders of the Army

were the two elected Consuls of Rome. Politics were nasty,

brutish, and highly competitive.

"Virtus:"

Roughly, courage and steadfastness

in daily life and on the battlefield. In war, a general

showed he had "virtus" by embracing personal danger. A Roman general

was at the front; he did not direct the war from

headquarters.

Relentlessness: pursue the enemy until it was defeated. No

negotiated peace.

Physical endurance: travel long distances on horseback on

poor roads or tracks, in all kinds of weather.

Psychological endurance: be away from Rome for years at a

time.

The favor of the gods: Military defeat meant the gods had

been offended, putting the Roman state in danger. A Roman commander

who lost was

worse than incompetent, he was a threat to all other Romans. |

|

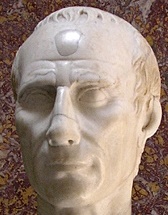

Julius Caesar

, 100-44 BC/span>.

Rome's

most brilliant of generals.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE LED

Who was in the

Army:

In very early Rome, the army

was composed of citizen-soldiers who served only part-time. temporary

military force.

Each

property-owning Roman citizen mobilized for war once a year.

16 campaign "seasons" --from the time the crops were sown

until they were ready to harvest-- were owed.

The citizen-soldier brought his own

equipment, weapons, and money for food. He could expect no pay

from the state.

The Romans

with the most property were in the cavalry, since a horse, its armament, and

upkeep were extra expenses beyond the reach of all but a

few.

Even within the infantry, soldiers were assigned by property. The heavy infantry, for example, required Class I property-- a helmet, round shield, greaves,

cuirass, spear, and sword.

As Rome expanded and began overseas campaigns and triumphs,

the Army recruited longer-serving, full-time soldiers, many

from the Allied provincial towns.

How they

fought:

The soldiers of the Roman Army were exceptional among

ancient armies in their patience and discipline as a unit.

Laying out the battle could take days, with the fighting

itself lasting hours and hours.

Once the battle started, hand to hand combat occurred as

the lines closed on each other.

In Roman tactics,

Roman soldiers did not rush headlong forward like a mob. Under

the screams and pushing of their officers, they moved

forward, fought, paused and backed up a little, then pushed forward

again.

As the two sides grappled, more soldiers from poured in, until one side gave in and fled.

The Roman commander held back a reserve. Those in the

middle of the scrum had to hold on, trapped, until the reserves

were sent in.

To keep the unit together under these frightening

conditions, harsh

training was routine.

Soldiers gave up their rights as

Roman citizens while in the military. Some of the citizen's

most important protections evaporated: a soldier could

be sentenced to a brutal beating for any reason. He could be put to death

without a trial.

Still, few Romans evaded their military duty or deserted. |

|

Roman Helmet, cone

shaped. 1st

c BC. The Balkans. The conical top protected the head.The

flap in the rear protected the neck. Not much protected the

eyes, nose, or lips.

National

Archeological Museum, Zagreb. Roman Helmet, cone

shaped. 1st

c BC. The Balkans. The conical top protected the head.The

flap in the rear protected the neck. Not much protected the

eyes, nose, or lips.

National

Archeological Museum, Zagreb.

Altar for Marcus Caelius Rufus. This

military unit had its "genius," a kind of guardian spirit

that guided and helped form 'esprit d'corps.' Berlin, German

History Museum. Altar for Marcus Caelius Rufus. This

military unit had its "genius," a kind of guardian spirit

that guided and helped form 'esprit d'corps.' Berlin, German

History Museum.

|

|

|

|

|

THE LOSERS

Who exactly were the opponents? Almost no

accounts from their side are left. Some tribes were illiterate. Sadder, those

who were literate, like the Etruscans, found their language and

culture erased by the triumphant Romans.

We

are left with the remains of a few mute wood huts and

shards of metal. But, thanks to modern archeology, art

history, and science, we can say that most of Rome's opponents

did not create peaceable kingdoms.

They maintained

their power internally by brute force and compulsion.

They aggressively sought others'

territories.

Sometimes,

they defeated the Roman Legions. Hannibal, as we know, was a brilliant battlefield general who kept

the Romans on the run inside Italy for years.

Some were

successful

in siege warfare.

They could adopt a scorched-earth approach, even of

innocent farmers, as ruthlessly as the Romans.

Like

the Romans, they sold the defeated into slavery and took

booty of all kinds, including women and children.

|

|

Roman Prisoner

of War.

The defeated

were sold into slavery.

Bronze. 2nd c AD,

British Museum. Roman Prisoner

of War.

The defeated

were sold into slavery.

Bronze. 2nd c AD,

British Museum.

|

|

|

|

|

REMEMBERING WAR:

The "Triumph"

"Remembrance" by

Rome of its military victories was about remembering who was

in charge: the very few members of an elite aristocracy.

The Roman state did not erect

memorials to ordinary soldiers who perished. There was no "Tomb

of the Unknown Soldier."

There were no signs of the

women, children, and by-standers who died in the wars.

The "Triumph" was the quintessential Roman signature of victory. A Roman Triumph

was a grand spectacle-parade-festival, the championship prize for a

commander.

The victorious

commander petitioned the Senate for

permission to stage his Triumph, which the general paid for. The Senate awarded about

300 Triumphs between 750 BC and the reign of Augustus,

700 years later.

Those refused might get a lesser "Ovation" or a special date

on the Roman calendar.

The Triumph was held

inside the city walls of Rome. The commander would be

clothed in purple, his head crowned by a laurel wreath. He

rode in a chariot drawn by four white horses. Since this

appeared to be flirting pretty close to

god-status, a runner whispered in his ear "You are but a

man."

The defeated, including families of the leader, were paraded

at the front in chains. They were on their way to execution.

Gold and silver, statues and artworks, from the looted

cities dazzled the throngs.

Large paintings of the crucial battles were carried along

the parade route; the ordinary

Roman could feel he was right there, on the battlefield.

Civil

War victories such as Pharsalus, Philippi, and Actium

presented a special problem. How could a commander parade fellow Romans,

aristocrats from the oldest families, in

shackles and on their way to execution. No "Triumph" was ever

awarded by the Senate to celebrate a Civil War

victory.

|

|

Triumph of

Marius

by G.B. Tiepolo, 1729.

New York

Met .

The

defeated King Jugurtha of North Africa, though in chains,

is wrapped in a crimson garment, his head raised high and

proud. Unlikely.

Jugurtha is on his way to death by starvation.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NOTABLE COMMANDERS |

|

|

| |

|

|

King Numa Pompilius

: The Road Not Taken

In

its early days, Rome was a semi-barbaric

place. It was peopled by the dispossessed, the desperate, and the

destitute.

Essentially, a place for those with nowhere else to go.

To rule over this bunch, there were (maybe) seven Kings of

Rome. Numa Pompilius (7th c BC.) was the second king. He reigned for 43 years,

creating order out of chaos, and gave a place for fugitives and runaway

slaves.

Numa founded the Temple of Janus.

The Temple's

doors were to be closed in peace and open in wartime. He

decided on peace. The Temple doors

were closed and remained closed for 40 years.

The legacy of Numa was "the road not taken" by the Romans.

Numa was unable to imprint upon the Romans either a willingness

or the

ability to live peaceably among their neighbors.

After Numa's reign, the Temple doors were open, that

is, "open to war" for nearly 500

years, as Rome fought year after year after year.

|

|

Numa

Pompilius Sacrificing a Goat.

Roman coin minted

around 100 BC.

Courtesy: VRoma. Numa

Pompilius Sacrificing a Goat.

Roman coin minted

around 100 BC.

Courtesy: VRoma.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Camillus

: The Second Founder of Rome

In Florence, Italy, you can see a 16th c fresco nearly a

wall long

inside the Palazzo Vecchio. It's

Camillus. Camillus is gloriously clad as a

near-mythological hero, atop a chariot pulled by white

horses , with too many legs, gazing at his (imagined) Roman

armament. The losers, bound with heads in conquered-slave position

are practically underneath the chariot.

Who was this Camillus?

Camillus led the Romans to their first great military

success, at Veii against the superior Etruscans. Then he

drove off the invading Gauls.

The Etruscan city-states dominated the central Italian peninsula. Veii, one of the

main city-states, was only a few miles north of Rome. Veii

gushed with wealth, and was both culturally and militarily

ahead of Rome. The two cities had fought on-and-off for

years.

Camillus crushed them through siege warfare. Their

civilization effectively ended.

Ten years later, Camillus, at that time in exile, returned

to lead the Romans against an invasion of Gauls. The Gauls

employed a frightening military style: they charged headlong

in a fury, scattering their opponents like bowling balls.

They sacked Rome, an traumatic event that was seared into

Rome's collective memory.

Camillus devised close combat tactics to counter the

ferocious charge of the Gauls, and apparently succeeded in

training his troops to stand their ground and fight back as

a group. Arriving too late to prevent the sack of Rome

(386 BC), he drove the Gauls away from the area before they

could assume control of the City and its hinterland.

Most importantly, Camillus persuaded the

discouraged people of Rome not to leave their destroyed town.

He was indeed "The Second Founder of Rome."

|

|

Marcus Furius

Camillus (c 450-365 BC)

Triumph over the

Etruscans at Veii.

Fresco by Francesco Salviato. 16th c.

Florence, Palazzo Vecchio.

Photo: Wikipedia.

Camillus was awarded

four military "triumphs." Five times he was named "dictator"

--a commander with temporary extraordinary powers to do

whatever was needed to save Rome.

Camillus died of

illness, possibly a

plague, aged 82.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Generals of the Roman Republic: Marius, Sulla, Pompey, and

Caesar

Marius, Sulla, Pompey, and

Julius Caesar: able, popular, and aggressive. They could

command large armies in different theaters, lead personally

on the battlefield, win where others could not, and

ruthlessly trump their peers in politics. Military fame and

the wealth

from victories, especially in the "East," propelled them far beyond

others of their

day.

These same characteristics led to fear and envy. To become

ever more wealthy, a general had to seek more commands,

bribing and intimidating to get them. For each person awarded

the military command, someone else equally ambitious lost

the chance. With

every victory against Rome's external enemies, one

more enemy at home was added. In Republican Rome, no one person was supposed to

gain too much permanent power. The actions of these

four, and later of Mark Anthony and Octavian (Augustus) led

to long, brutal civil wars. At the end, the heart of the

system of shared power was dead. |

|

|

|

|

|

Marius |

|

Pompey |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sulla |

|

Caesar |

|

|

|

|

|

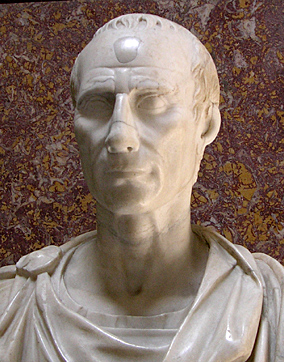

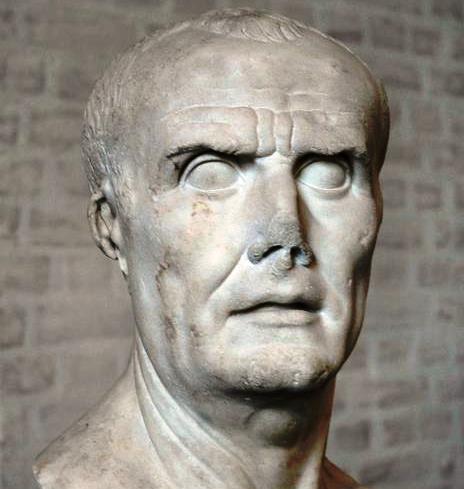

Marius: the Hero of the People

Was General Marius the

"ideal" type of Roman commander? He's looking straight ahead,

with intense, bulging eyes. He has a furrowed brow and bushy

eyebrows, a square jaw, somewhat sunken cheeks, and a large

forehead. Probably he had a strong nose. The sculptor has given

us a man of "virtus," the manly courage and

steadfastness that the Romans valued so highly in their military

leaders.

Marius showed his brilliance as a general three times: in

Spain, in North Africa, and in defense of the City of Rome.

He reformed Rome's political institutions and its Army, making both more favorable to ordinary Romans.

On the darker side, he plunged Rome into terrible Civil

Wars.

Marius started his military ascendancy in Spain. Spain had a

vital asset: silver. Marius fought brutal, guerrilla-style warfare

against native inhabitants of Spain. His reward: silver

mines.

Marius next took on the threat to Rome's grain supply by the

wily King of Numidia,

Jugurtha. Fighting in North Africa, Marius captured the

King and sent him to Rome, where Jugurtha was starved to

death.

Back to Rome: Tribes from northern Europe, the Cimbri and the Teutones, were migrating southward into southern France. When the tribes

unexpectedly decimated all three of the Roman Armies sent to

stop them, the road to Rome lay open. Marius was sent

after them.

He defeated the tribes decisively. Delirious with relief,

the Romans awarded Marius not one but two triumphal parades.

Marius and the common soldier: Rome's traditional,

summer-service Army had come from property-owning small

farmers. Marius turned it into a long-serving Army,

recruited from Rome's poorest citizens, those with little future.

They joined up for a regular

source of income, food, a chance for booty, and land upon

discharge. They became loyal to him rather than to the Roman Senate and People.

The new, much poorer "boots on the ground" recruit

couldn't afford equipment. Marius organized a central armory to issue each

soldier a pilum (javelin) and a pugio (dagger).

Marius asked Rome to give its veterans, upon discharge, a

plot from Rome's public domain lands to support themselves

and their families.

|

|

Caius

Marius, 157-86 BC. Caius

Marius, 157-86 BC.

Marius started gloriously, a genuine war hero and consul an

unprecedented 7 times, but ended badly.

His plan to give land to the veterans lay the ground for the Civil

Wars. Others were already using the public land for private

profit. They deeply resented losing their privileges.

In his later consulships, he became increasingly

paranoid. Plutarch tells us Marius "thirsted for blood, and

kept on killing all whom he held in any suspicion."

Finally, out of sheer greed, he unseated the rightful

military commander in the East, Sulla. With this act, he took Rome

into the civil conflict that punched very deep holes into Rome's social

and political fabric.

Marius died seventeen days into his 7th consulship, at age

71.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

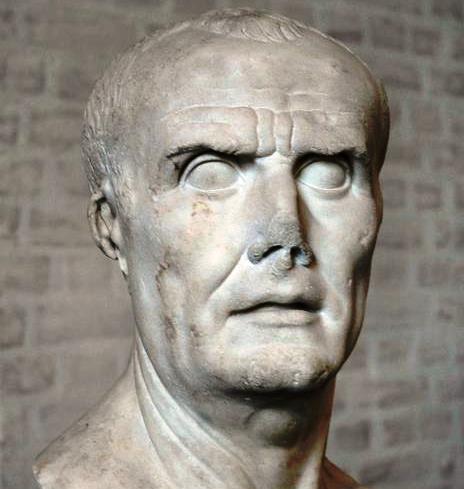

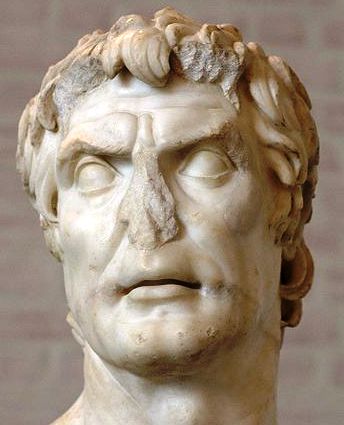

Sulla:

The General Who

Killed the Republic

In Munich, you can

see an especially ferocious portrait bust. This is Sulla, the man who

spelled the end of the Republic. The eyebrows jut in an

upward slash, the piercing eyes bulge, the nose must have been

substantial. This was a person you would want to give a wide

berth to.

Sulla had first made his military reputation in North Africa

under Marius in defeating Jugurtha, the King of Numidia.

Jugurtha seemed

to excel in bribing Rome's highest officials. Sulla, under

Marius' leadership, captured Jugurtha through better

treachery--his father-in-law coughed him up.

In 101 BC Sulla joined Marius in the

campaigns against the Germanic tribes. He was key in

defeating the Cimbri. The Cimbri tribe, women and

children as well as the male warriors, was extinguished from

the face of the earth. Rome

breathed a sigh of relief.

In southern Italy, Rome's allies, who were not "citizens" of

Rome, revolted over unequal taxation. After all, they were

allies. The Romans thought otherwise--an ally to them was

someone they had conquered and then allowed to exist-- and

sent Sulla to defeat them.

Was Sulla becoming too successful? The Senate and Sulla

tangled, twice. The Senate, led by Marius, took away his

command over the Eastern army. Sulla, tossing aside

centuries of Roman tradition and law, led his soldiers in a

"March on Rome." The Roman government sent emissaries to

reason with him. His soldiers stoned them to death. Sulla

won. Marius fled.

The second time they tangled,

Sulla engaged in scorched earth policy from Athens to Rome,

sparing neither Roman citizen nor ally. Outside the Colline Gate in Rome, Sulla won

a final battle against the Roman Senate and their

supporters.

He became

"dictator," the first in 120 years. His victor's

speech to the cowering Senate was accompanied by the screams

of thousands of soldiers being executed a short

distance away in the Forum.

As dictator, Sulla "cleansed" the elite of Rome. The independence of the old Senate and of elected Roman

officials was broken, the economic underpinnings of rivals

wiped out. Sulla's bloodbaths and confiscations against fellow

Romans scarred Roman consciousness for the next 80 years.

|

|

Sulla

(Lucius Cornelius

Sulla, 140-78 BC).

Munich: Glypothek.

Sulla had exceptionally fair skin that showed

red marks later in life, blue or grey eyes, and a mane of reddish-blond

hair. He was fond of good food and dancers and

actresses, a dissolute life-style for Romans.

Sulla was the first Roman general to lead a Roman Army

against the city of Rome and its duly elected government.

The author Pausanias related several

centuries later, with a hint of relish, that Sulla died

"seething with maggots (possibly

lice).

His early apparent good luck came round to so

terrible an end."

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

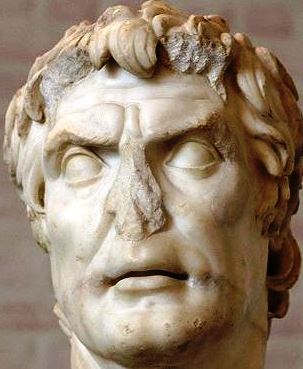

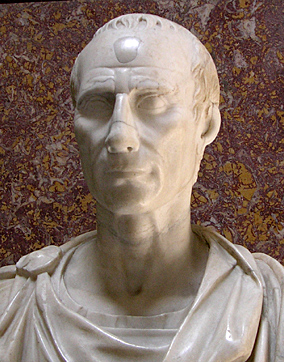

Pompey the Great

In this portrait bust, the

sculptor has given Pompey a self-satisfied look. As well he

might: Pompey was called "Pompey the Great" for

good reason. At a young age, he raised a private Army and refused

to disband it after it won again and again in the long Roman

Civil Wars.

The Senate, not knowing quite what to do with him and his

Army, decided to forgive all and make his acts legal. They

gave him plum military assignments and celebrated his victories with three "triumphs."

Pompey's last

triumph was given for his generalship against the most

resilient of foes, Mithridates.

Mithridates was the King of Pontus (in northern Turkey on

the south shore of the Black Sea). Mithridates had committed

an act of atrocity horrifying even by ancient standards.

After invading the Roman province of "Asia" (modern Turkey),

he had ordered the massacre of every Roman and Italian man,

woman, and child, perhaps 80,000 total.

Mithridates and Rome had been at war for 23 years when Pompey

arrived. Pompey swept through Asia , and gave Mithridates

his final defeat. Pompey claimed to

have killed, captured, or defeated over 12 million people in

his Eastern campaigns, and accepted the surrender of 1500

towns and fortified places.

Pompey returned from Asia as one of the wealthiest man in

Rome. His ostentatious third "triumph," for his Asia

victories, started on his 45th birthday and lasted two

days. He rode in the parade in a chariot studded

with pearls. A portrait of him, made of rare pearls and

gemstones was prominently displayed. The captured silver rolling past the

spectators was equal to the annual tax revenue of the entire

Roman world.

When the throne of Mithridates and a gold statue of the

defeated King appeared, no one could doubt that Pompey had made

Rome into a true world empire.

|

|

Pompey the Great,

(Gnaeus Pompeius

Magnus, 106 BC-48 BC). Ny Carlsburg Glyptothek, Copenhagen.

Photo: courtesy

Penelope@chicago.edu

Pompey, once a

great general, died a sad death.

Pompey married the only daughter of

Julius Caesar. They were very much in love. When she died

at a young age in childbirth, Pompey and Caesar's bond broke, and the

two led different sides in the subsequent civil war.

Pompey panicked against Caesar at the battle at Pharsalus, northwest of Athens, and lost.

Committing the worst of all acts for a Roman General, he

abandoned his army and fled to Eqypt. The

Egyptians

assassinated Pompey and presented his

head to Caesar. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Julius Caesar

Americans know Julius Caesar for three things: "All Gaul is

divided into three parts," the opening words of his

Gallic Wars;

his affair with Cleopatra; and his murder on the Ides of

March, including Shakespeare's words "Et tu, Brute?"

As a military

commander,

Caesar owned the Roman trait of "virtus" --physical

courage, military skills, and moral leadership over his

troops. He could deploy his army with control, paying

attention to the smallest details of the units and the

combat at hand.

His ability to see options on the battlefield and make the

brilliant decision was uncanny, and Caesar celebrated four

military "triumphs" for his accomplishments. The first for

victories in Gaul against

many large tribes. The second for victories in Eqypt. The

third for his battles in Asia against the Asian ruler

Pontus. The fourth for victory in North Africa against the King of Numidia.

Some of his most important victories--those of the

Roman Civil Wars--could not be mentioned.

At 19, he

received the rarely-award

"corona civica" for personal bravery.

A simple oak wreath, the

corona civica

marked a

solider as a true hero, one who had saved the lives of other Roman soldiers

at considerable risk to himself. When the hero entered a Roman

event such as a festival, all attending, even Senators, rose to their feet

in gratitude and respect.

Caesar was just a fearless at 52, when he personally led his Army to defeat the great Pompey at the

battle of Pharsalus in the Civil Wars.

Charismatic and

empathetic, Caesar connected with his troops. He addressed

them as "comrades," and sometimes as "citizens," never as

"soldiers" or "men." Caesar

led his columns in the field, sometimes on

horseback, often on foot, showing his

officers and men that he expected of himself

exactly what he expected of them.

He

trained with his men, leading them on foot,

leading at night, leading in the rain, leading over

difficult terrain. He slept in the open air with his

soldiers and rode with his cavalry for hours on end, even

though he suffered bouts of epilepsy and other ill health.

Julius Caesar didn't think he would have any problem with

the gods: his father's family were descended, so

he said, from Venus herself.

|

|

Gaius

Julius Caesar, (100 BC-44 BC).

Caesar was not particularly wealthy before he became Consul

and Commander, but he was witty and charming to men and to

women.

Rome's most aristocratic women found him

irresistible. Women could not play an overt role in

politics, but their connections furthered Caesar's political and military careers.

He wrote and

spoke (orated) well. Even the great Cicero admired his

talents. His connections backed him. He backed himself by

taking on huge debt to win in politics.

Caesar was thought to be one of Rome's great

lovers. His affairs could be short or long. He

married three times: to Cornelia, to Pompeia, and to Calpurnia,

and had a long affair with Servilia, mother of his assassin

Brutus. And then there was Cleopatra...

|

|

|

|

|

|

NOTABLE LOSERS |

|

|

The Etruscans

The Etruscans were an older, more advanced society than the

early Romans. At one time, an Etruscan royal dynasty, the Tarquins,

may have ruled Rome, producing "Etruscan Rome". The

art and architecture of the early Roman city was certainly

Etruscan and Greek, produced by Etruscan craftsmen.

In time,

the balance swung. Rome conquered Etruria, and Etruria

became Roman, rather than Rome becoming Etruscan.

The city built by the Etruscans became their nemesis and

conqueror. Over a period of 300 years, all of the various

Etruscan city-states fell to Rome.

Enmity and jealousy

pulled them apart. Their own priests said their culture's

lifespan was at an end. By 90 BC Etruria had declined into

just another region of Italy, ruled by the Romans.

Etruscan

culture and language were erased from the face of the earth.

|

|

Roman Triumph over the Etruscans at Veii.

16th c fresco by Francesco Salviato. Florence, Palazzo Vecchio. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pyrrhus

The term "Pyrrhic Victory" comes from one of the

strongest opponents of the early Romans: Pyrrhus, King of

Epirus, in northwestern Greece.

The tribes, settlements, and

cities of the Italian Peninsula were being threatened by

the Romans. They hired Pyrrhus, a Greek King, to get rid of the

Romans since they could not do so themselves. He almost

succeeded. He twice defeated the well-organized and numerous

Romans, at the Heraclea in 280 BC and at Asculum in 279.

Pyrrhus put together a modern-looking army--

professional soldiers, who used pikes in a phalanx, with war

elephants to supply the fear-factor and cavalry for

mobility. As a general, he was a far cry from the

tribal chieftain or the faction-bound city-state that the

Romans easily toppled.

The cost to Pyrrhus from these victories was heavy.

After he Battle of Asculum,

Pyrrhus lost his headquarters camp. Personally, he suffered a life-threatening javelin wound.

Pyrrhus

allegedly said that one more such triumph against the

Romans would ruin him.

Worse, the Romans refused to give up and come to terms after

their two defeats. This behavior defied the ancient world's

military codes. Pyrrhus went home to Greece without a declared

victory. In the end, he was not considered a winner.

With Pyrrhus out of the picture, the Romans rapidly defeated

those who had hired or sided with him. Roman hegemony over

the Italian peninsula appeared unstoppable.

|

|

Pyrrhus, King

of Epirus, Greece.

( 319-272

BC)Bust, National Archeological Museum of Naples.

Courtesy:

Wikipedia.

After

'defeating' the Romans, King Pyrrhus returned to the Greek

world. While fighting in the city of Argos, a woman on top

of a house flung a tile down onto him. Down he went; an

enemy soldier ineptly severed his head from his body.

No one thought it disgraceful. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hannibal

: the Second Punic War

"The elephants go on and smash everything under

their feet: they (i.e., the Roman infantry) go like tomato

juice..."

On

Hannibal's wine-fed elephants, by S. Frankello, German

elephant trainer. His video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=0gbPIyCuGTAHannibal of Carthage: to us,

the general with the most exotic, unbelievable, heroic

story-line: he leads a large army through the Alps, in

winter, with a corps of elephants. After descending to the

other side, in Rome’s home court, he smashes the waiting

Roman Army.

Hannibal: to the Romans, this

commander is nuts. Crossing a high mountain range in

winter? With a large army to supply and keep together?

Running a gauntlet of mountain tribes situated high above in

the narrow passes? With 37 elephants, not known to like snow

and cold? With no supply base or allies on the Italian side?

No

Roman general could have thought Hannibal was much of a

threat. Rome was the “new-style” power: super-offensive,

coming back again and again with endless supplies of

manpower, until complete victory. The quality of generalship

did not much matter. “Old-style” powers, like

Carthage, could afford to lose only around 5-10% of

their force, so they maneuvered, engaged in siege warfare,

and negotiated settlements.

The Roman Army trained their

soldiers in close, hand-to-hand field combat. Their

large-scale units could operate in controlled, disciplined

formations. How could an "Old-style" army survive even

a week in Italy?

Hannibal broke the mold. He

proved that brilliant generalship could win the day. In

three stunning victories in Italy within two years—at Trebia, Trasimene,

Cannae-- the Romans were decimated. Then sucked into an 18

year war that claimed as many as 1/3 of all Roman males.

Eventually, the Romans

wised up and attacked Carthage even though Hannibal was

still at large in Italy. Hannibal returned to Carthage to

defend his homeland but lost the battle of Zama. After

Carthage's surrender, he lived another 20 years. He entered

politics, became a reformer, then fell afoul of the Roman

authorities in Carthage. He fled to Asia (modern Turkey),

where he served various kings fighting the Romans. Soon he

was on Rome's Most Wanted list. About to be fingered, he

committed suicide around age 66.

Of the 37

original elephants, those who made it over the Alps died in their

first year in Italy from an unexpected prolonged freeze.

|

|

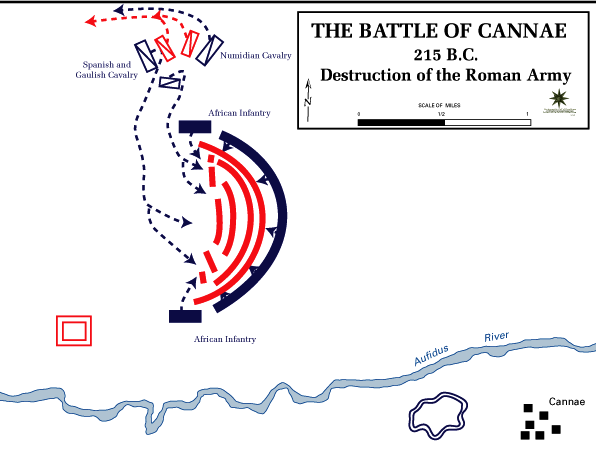

Hannibal defeats

the Romans at the battle of Cannae, 216 BC. The

Carthaginians are shown in blue; the Romans in red.

Detail of diagram courtesy

of US Military Academy.

I've always been

moved by how little evidence exists today for battles where

thousands lost their lives.Trebia,Trasimene, and Cannae are no different.

Little archeological evidence has been uncovered--few pieces of

armor, projectiles, or remains of the many soldiers who

perished.

For Cannae, no memoirs of those who fought survive. What we

know of the battle comes from two ancient Romans writing

much later: Polybius and Livy. Nothing from the Carthaginian

side survives.

Strength and

casualties (approximate)

Trebia: Hannibal 30,000 men; 4,000 lost

Rome: 42,000

men; 32,000 lost

Trasimene: Hannibal: 30-50,000 men; 1500 lost

Rome: 30-40,000 men; 15-30,000 lost

Cannae: Hannibal: 50,000; 5500 lost

Romans:

86,000 men; 67,000 lost

The casualty rate at Cannae--for a single day's

fighting, as a percent of the force-- was not

reached again in the West until World War I.

|

|

|

|

|

SOURCES

For the general reader:

The best single volume is

by Jonathan P.

Roth,

Roman Warfare: the Cambridge Introduction to Roman Warfare.

2009

Adrian Goldsworthy

has written a number of recent books on warfare and the army

in the early period that are both interesting to read and

rely on primary resources. On the Army, try his:

The Roman Army at War;

Roman Warfare; and

In the Name of

Rome.

Goldsworthy's biographies

include: Anthony

and Cleopatra; (Julius) Caesar, The Life of a Colossus;

and Augustus.

Battle-oriented ones are:

The Fall of Carthage

and the Punic Wars, and Cannae.

Scullard, H. H. , The Elephant in the Greek and Roman World.

1974.

For more advanced readers:

Cornell,T. J., The

Beginnings of Rome.

1975.

Galinksy, Karl,

Augustus.

2012.

Harris, William.V.,

Rome in

Etruria and Umbria.

(1971).

Osgood, Josiah,

Caesar's Legacy: Civil

War and the Emergence of the Roman Empire.

2006.

Rich, John and D. Graham Shipley,

War and Society in the

Roman World. 1993.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Updated 21-July-2016. You may contact me, Nancy Padgett,

at

NJPadgett@gmail.com. |

|

To read the primary sources:

Sage,

Michael, The

Republican Roman Army: a Sourcebook.

2008

Horace translation by A.S. Kline,

Horace: The

Epodes and Carmen Saeculare

from his web site

http://www.poetryintranslation.com

Internet

resources

Bryn Mawr Classical Review

http://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/

Lacus Curtius

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/home.html

Livius.org

http://www.livius.org/

For casual readers and wargame buffs:

BBC History Magazine

http://www.historyextra.com/category/topics/era/romans

Ancient Warfare

http://www.karwansaraypublishers.com/pw/ancient-warfare/

UNRV

http://www.unrv.com/

|

|

|

|

|

|