|

|

| |

Minerva, Roman goddess.

Alabaster, basalt, luna marble bust. 1st c BC. National Museum

of Rome, Museo Massimo. Rome.

Courtesy: VRoma

Highlights

* There were many gods in many places,

with more created all the time.

* Humans had a public relationship

with the gods, not a private, spiritual one.

* The purpose of Roman religion was to

gain benevolence from these powerful spirits, to ensure the

safety of the state and the family.

* The later Emperors thought they

themselves were gods, and built elaborate temples to show it.

Glossary

of Roman Religion

Web

Resources and Books |

|

Roman Religion: The Ancient Gods

In Rome, I took a

bus from the Colosseum to the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, one of

the National Museums of Rome, located near the central train

station and the Baths of Diocletian. So simple to get there, not

so simple to get elsewhere afterwards-the City's transportation

hub centered on the train station is large and chaotic. The magnetic lure

of ancient Rome prevailed.

Inside the building, past the guard station, right in front of

me--a giant statue. Minerva, goddess. Glowing in color, not

chilled in snow.

Who was this creature? Minerva, goddess.

To the Greeks, Athena.

My next hunt was on.

Were there many gods? What

good were they? What did they

look like?

Could you

talk to a god? Could

a god help you out?

Harm your enemy?

What if you made a god

angry?

Why so many

priests?

What went on at

a sacrifice?

Where did Romans worship?

Could a

human become a Roman god?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The number of Roman

gods

The Romans worshipped an astonishing number of gods and

goddesses.

Gods here, goddesses there--there was no end of the way

they kept popping up in temples, groves of trees, babbling

brooks and springs, crossroads, caves, theaters, and urban baths.

A good place to see them is the Vatican Museum in Rome. It's

famous for far more than the Sistine Chapel. Off I went to

spend a day at the Vatican Museums. Here's what I saw, when I

wasn't crushed by the good-natured crowds. Everyone loves a god and goddess.

Some gods shared territory. Mars, Jupiter, Bellona and Victoria, even

Juno, and later Mithras were all worshipped in connection with

war.

Many had more than one assignment.

Juno had an especially large portfolio--goddess of war, of marriage, of new beginnings, of youthfulness

and liveliness, as protector of the community.

To the Roman way of thinking, a multi-purpose god was only

natural. Very different strands of life were part of a whole in their society.

There were "great" gods like Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, and narrow-bore gods like Imporcitor, the god of "ploughing with

wide furrows."

Most did not have much personality or character.

|

|

Sightseers

throng to the galleries of

the Ancients. The Vatican Museums, Rome.

The Gigantic Hercules.

Bronze. Roman.

1st c

AD. Vatican Museums.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A surprise to me: more gods and their cults

needed to be created all the time.

To the Romans, this made perfect sense: in the ancient world, gods and

goddesses had active sex lives. Of course they produced god-children.

The process for becoming a recognized god was straightforward.

An

existing god told the humans it was time to do something, usually

through a sign like a major military victory.

Since a Roman could not worship a god unless the god was recognized by the state, the Senate

got busy and reviewed the

proposed new god.

Eventually, the Romans lost track of

their multiplying gods and goddesses.

In the 1st century BC, the

Roman writer Varro tackled the mess. Varro wrote the Wikipedia of its day

on the subject, his vast

Divine Antiquities.

|

|

Visitors dwarfed by the gods

Juno

and Hercules. Vatican Museums, Rome.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Purpose of the gods?

Did the gods have nothing better to do than clutter up the lives

of the humans?

To the Romans, their gods were powerful

and somewhat unpredictable

forces outside of human society that could impact Rome's very existence.

The gods didn't provide an Adam-and-Eve creation story, nor promise

redemption like the Christ story, nor provide an code of ethics that

could make you a better person.

To the state, the gods could deal a victory in war; to

the community, a good harvest; to the family, a successful childbirth.

From these powerful gods, the fearful Romans sought "benevolence."

Why did a Roman need benevolence? Though the gods may not have

always been

capricious, the everyday world of a Roman appeared so. With an

expected lifespan of only 25 years, children died all around

you. Those who survived were malnourished. Illness and injury had few

effective treatments. Threats of invasion, burrowed deep in the Roman

collective memory, still seemed imminent.

The more

protection from a god, the better off you might be.

|

|

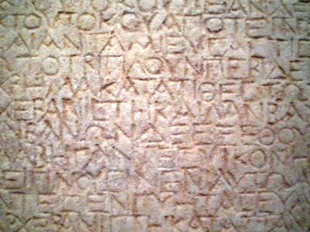

Rules for Worship of Hercules.

Marble. Roman. 2nd c AD. Getty Villa. (Partial). This marble

tablet shows the statutes of a religious association that worshipped

Hercules.

The text includes rules of conduct--you couldn't get rowdy and engage in

fighting during the meeting, and you must wear a wreath in honor of

Hercules.

The Romans were keenly interested in wealth and status.

The tablet

explained the association's endowment and how it would be spent. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What did a Roman god look like?

Gods looked mostly like humans, preferably Roman humans with

maybe some

Greek or Etruscan influence.

Minerva, the goddess pictured at the top of this page, looks a lot like

a human woman. Though supersized-- and with a strikingly big foot-- she is dressed in

the clothing

fashion of the day.

A few ancient gods changed form, like the

Greek Zeus (the Roman Jupiter) who changed from a human-like god form

into a bull to lure away a young human woman known

as "Europa."

The god Mithras, though he was born from a stone, emerged as a

fully-formed human youth.

|

|

Mithras

born from a rock.

Marble, 180-192 AD. From the area of S.

Stefano Rotondo, Rome.

Courtesy:

Wikipedia Commons |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Talking to a Roman god

Talking to the gods was a difficult

business.

Everything in the ritual had to performed without the

slightest variation or error. The right mumbo-jumbo said just so

by the right person at the right time in the right place. The Romans must have had

an obsessive-compulsive gene in their blood.

Could a god help you out?

The gods may or may not help you out in a specific situation.

Adornments might assist. From the time

he was 9 days old until he was 16 years of age, Roman boys wore

a bulla on a chain around their necks. Nestled inside the bulla

were amulets to channel the energy of a divinity and

protect against evil forces.

|

|

Bulla-amulet.

Roman, 1st C AD.

Gold. Palazzo Massimo, Rome.

Courtesy: VRoma.

|

|

|

|

|

Divine Friends with Benefits

Emperors chose a personal god and blatantly (for some,

desperately) advertised the

"special relationship." Domitian had Minerva, Augustus claimed

Apollo, Diocletian roped in Jupiter. Nero thought he WAS a god. The protection plan

evidently had limits: Domitian was assassinated and the memory

of him officially X'ed out.

A Roman might change gods if he felt he was under the wrong one.

Emperor Constantine initially chose the Sun god, Sol. At a

crucial point in his military campaign in Italy, he switched to

the Christian God. Constantine won. Christianity won. The other

gods lost--Christianity in the later Roman Empire tossed

out the old Roman religions and gods.

|

|

Apollo,

special divine friend of Emperor Augustus.

Fresco fragment from the

Palatine. Roman. Palatine Museum, Rome.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Could a god harm your enemy for you?

You could not demand a Roman god to allow you to harm someone

else. Harming someone else was "impietas"

The worst form of "impietas" was to

kill a member of one's family. Emperor Nero murdered his mother,

Agrippina. Born with a sign of luck-- a double canine tooth in her upper right

jaw--Agrippina was appointed a priestess of the cult of

her late, deified husband, the Emperor Claudius. Neither her

good-luck tooth nor her status as priestess protected her from her

murderous son.

Afterward Agrippina was murdered, Nero's friends noticed

he was tormented "by the gods." We might say by guilt.

|

|

Agrippina

the Younger, mother of Emperor Nero.

Roman. Marble. Getty

Villa, Malibu.

In

Roman society you had a duty to respect another person, at least a

person of your own rank or better.

How you could treat those beneath you in status, or an enemy of the

state,

was a different matter.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What if you made the gods angry?

The gods were serious about "impietas."

A grave "impietas" was to knowingly violate a divine

rite. For this, the gods might avenge themselves upon Roman

society and state as a whole, not just upon the offending

individual.

Recall the legend of Publius Claudius, the Roman consul and general who went into

battle against the Carthaginians even though the signs from the gods clearly

said "halt": the sacred chickens had refused to eat properly!

The grains of cake did not fall from their mouths just so! Claudius, fed up, ordered

the chickies thrown into the sea, declaring: "If they will not eat, let

them drink."

The Romans weren't merely defeated, they were routed. And Publius Claudius? He was tried in Rome for

"impietas." Fined and

sent into exile (i.e., tossed out of the community and without his wealth,) he committed suicide. |

|

Sacred Chickens in their Cage.

Photo of a marble table, Roman.

Source: University of Chicago Libaries,

Speculum Magazine.

In Latin, the cage is called a "Pullaria

cavea." A "pullarius" was the bird-handler. His duties were

to open the cage and feed the sacred chickens in a particular manner.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Why were there so many priests?

And priestesses and Vestal Virgins!

The gods

ruled the fate of the state and therefore the Roman state had to regulate

itself according to religion. The Romans needed to know the "will of the gods"

before embarking on any human enterprise, large or small.

Passing laws, holding elections, and discussing public policy

took place within spaces defined by priests. The Senate could

meet in one of several places, but not just any old place: one

that had been defined by the priests as not offensive to the gods.

To start any Senate meeting-- or start a war-- a Senator-priest

had to invoke the proper religious ritual.

A religion this pervasive would of course require lots of

priests!

A priest was expected to come from the political-military-social

elite that governed Rome. For an elite Roman male, the priesthood was not

his sole occupation; it was part of his normal life.

Priesthoods were organized into colleges, each with their own

sphere of influence. There was no "chief priest."

Places in the

priesthoods followed the gradations of the elite's social hierarchy.

In the later Empire, the most important priesthoods were

attached to the Imperial cult, worshipping the ruling Emperor

and his family as divine.

But priests had to be careful what they forecast: even an

Etruscan haruspex did not lightly prophesy the demise of a

Roman Emperor.

|

|

Coin

struck by Caesar c 45 BC, showing himself as

Pontifex Maximus.

Quick

Glance at Priests and Prophets:

For more detail see the

glossary on Roman religion below.

The major priestly groups:

Augurs: "took the auspices" or discerned the will

of the gods, when an important event, such as a military battle, loomed.

Duoviri, decemviri, and quindecimiviri: advised the

Senate on reports of prodigies.

Flamines: Individual priests

for the early gods, Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus.

Pontifices: controlled the calendar and kept the record of

public events.

Ordinary priests: Their role was to

show up and be seen as representatives of the political and military

elite.

Haruspex: An Etruscan highly specialized in the art of

prophecy. A Haruspex knew a mountain of technical mumbo-jumbo. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

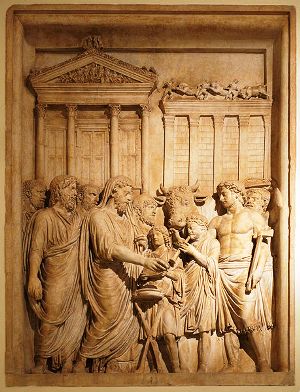

What went on at a sacrifice?

In Rome, I went to see visuals about

Roman religious sacrifice at the Capitoline Museum and at the

Curia in the Roman Forum. This lovely Roman marble fragment pictured

right is at the

Capitoline. What I remember is the bull. How cooperative he seems! The

sheer calmness of the beast looms over the ferocity of the humans. As a

child growing up, I recall our cow Josie was not at all gentle. Perhaps

Josie knew where she was going to end up, and this bull doesn't.

A sacrifice in Roman religion offered up an animal, not a human. Bulls,

cows, sheep, and pigs seem to calmly take their

place in the ritual.

The animals must be one of two colors,

black or white. Cattle, and only oxen at that, are offered to

Jupiter. Mars gets a bull, and Vulcan a calf.

Female animals should be

offered to female deities, and male animals to male gods.

The ceremony of the sacrifice reflects the Roman social order. The

magistrate-augur is in charge of the ceremony, since he is responsible for

mediating the contact with the god. Here's what happened:

At the Temple of Jupiter, the sacrifice is made on a stone altar in

front of the temple, not inside it. The audience watches from the plaza below.

The magistrate pours an offering of wine from a small dish onto a fire

burning on the altar. Two young boys carry a box with the incense that

the magistrate then tosses into the fire.

Pliny tells us that next:

"The magistrate says a specified, ritual prayer. To prevent a single word

from being omitted or spoken in the wrong place, another priest reads it

out first from a script, another is posted as guard to keep watch, and a

third ensures silence is maintained. A piper plays so that nothing else

is heard except the prayer."

The augur escapes the unpleasant work of the sacrifice himself,

naturally, being an aristocrat. Specialized slaves owned by the state, known as the 'victim handlers' holds down the

head of the by-now suspicious animal while the other stuns it with a mallet. As

the animal falls,

a third slits its throat.

Once the animal is dead, it is cut open and

inspected to ensure it is healthy. If the ceremony calls for a prophecy, a haruspex

inspects the liver and compared it with a map of the sky. Sheep are

often used by the Etruscans.

If the animal's liver passed muster, it is burnt on the fire as a meal to

the god. The rest of the animal is cooked and eaten by the magistrates

and his associates, sometimes with distributions to others attending the ceremony.

This last act, a meal shared between the god and the people, renews the relationship between the

deity and Rome.

|

|

Religious sacrifice of a bull.

Bas-Relief. 2c AD. Capitoline Museum, Rome.

Courtesy: Wikipedia Commons.

This bull will be sacrificed by the Emperor

himself, Marcus Aurelius.

The piper plays to silence the audience.

The

fierce-looking guy leading the bull is a priest, and the boy in the

middle is offering the ritual incense box to the Emperor.

The Temple of Jupiter

Greatest and Best is in the background.

Sheep used in animal sacrifice.

Marble frieze known as the Plutei of Trajan. Roman. Curia, Roman

Forum, Rome.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Where did the Romans worship?

Religion was overwhelmingly a public affair, not a

private moment with one's Almighty.

A Roman could not turn around without running into, or smelling, a

sacred space.

Plowing the fields, walking to the market, at a crossroads

in the middle of nowhere, at one of the baths in the city, in your home,

carrying out public and administrative business, festivals and triumphs:

no escape from a god, sprite, or genius.

Who built

all these temples? The Roman social elite, not the state, was expected

to build them--no wonder there were so many.

The elite tossed up temples to celebrate

military victory, or in honor of a family member, or just

because they could financially. A triumphant general produced grand

temples with his own funds, or rather from the booty gained from

his military campaign.

A Roman city's main temple was often the first visible building in a city, gleaming

on top of an acropolis. One was always "looking up" to the

gods.

In Rome, the Temple of Jupiter Best and

Greatest, by far larger than the Parthenon, sat on top of the Capitoline

Hill. It could be seen for miles. What little of it exists

today is located inside the Capitoline Museum itself.

Other temples of normal-enormous size clustered in the center of a

city. Temples

towered over the humans, and not by accident.

Temples were designed to inspire awe for the state as well as respect

for the gods. All over Rome, I saw remnants of those huge temples--not

only those in the Forum, otherwise surrounded by rubble, but those still

in use like Hadrian's temple, pictured right.

Temples were built, rebuilt, redesigned,

enlarged, and rebuilt,

again and again as Rome prospered. Once Etruscan, Roman temple

architecture became increasingly Greek. The materials became exotic, the

architectural detail elaborate, as Emperors thrust emblems

of their magnificence and authority in the public's face.

Once back at home, you would worship

your own household gods,

the household genius, a household Vesta, and the spirits of your dead

ancestors.

|

|

Temple of Jupiter Best and Greatest (reconstruction). Era of Vespasian,

1st c AD.

Rome was extremeley crowded, temple after temple,

building on top of building.

The Temple of Jupiter lasted 900

years and then was destroyed by invasions, Christian recycling, and

time.

Temple of Hadrian

.

Rome; currently the Rome Stock

Exchange.

The columns tower over 48 feet in the air, with another 16 feet below

the current pavement level.

Temple of Vespasian

(ruins).

Roman Forum. Rome.

The height of Temple's columns measure about 8 times that of a

present-day Western, adult male. (Our mere mortal is standing on a high

viewing platform.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Humans into gods

The Emperor Vespasian, as he was expiring, declared,

"Oh, I think I am becoming a god."

But most Romans thought "no god arises from man."

Julius Caesar, who thought he was descended from Venus, upset this

stricture. He had politically powerful

friends who declared him "divine."

First Julius Caesar. Next, his successor Augustus,

whose wife Livia rewarded a senator with an outrageous fortune for

stating he saw Augustus ascend to heaven. After that, divinity for any

Emperor was almost a done-deal.

The slippery slope eventually included non-rulers: a wife or other

female relative of an Emperor was often declared divine, "suggested" by the

Emperor and declared so by the Senate.

Later Emperors did not make much effort to wait until death before

assuming the trappings of their upcoming divineness. The

probably-disturbed, and most certainly brutal and lazy, Emperor Commodus

converted the great Colossus statue of Nero, over 100 feet tall, into a

statue of himself as Hercules.

|

|

Emperor Vespasian.

Colossal head. Marble. Roman.

Displayed

at the Curia, the Roman Forum, Rome.

Visitors at Exhibit of Emperor-Gods,

including Vespasian and Titus.

Curia, Roman Forum, Rome. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Glossary of Roman Religion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Augurs:

Augurs

sought revelations and "advice" from the gods about the immediate

future. Through "taking of the auspices," the augurs established the

will of the gods about actions the Romans wanted to take. For example,

should a Roman general engage in battle with the enemy on a particular

day.

What an augur did: augurs observed

natural phenomena. The flight and activity of birds, thunder and

lightning, and feeding patterns of the sacred chickens held special

status.

The augur had to

follow

written instruction from his manual. The manuals contained the proper

techniques for the ritual and how to interpret the results. Signs given

by the gods to the augur were good only

for one day.

Duoviri, decemviri, and quindecimiviri:

a group of distinguished Senator-priests who

advised the Senate on reports of prodigies. Prodigies were events which the Romans

considered "unnatural," such as "rains of blood" or "monstrous

births."

Epulones:

specialized priests in charge of the

rituals of the Roman games and of the feast of Jupiter, Rome's most

important god. Along with the

pontifices, the augurs, and the duoviri, the epulones made up the four major

'colleges' of priests.

Fetiales:

Priests who prayed to the gods for success in war.

Flamines: a special group of

pontifices. Originally flamines were individual priests for the Roman gods

Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus. As a distinguishing mark, the flamines wore a cap

with a piece of olive wood projecting from its top.

Haruspex:

A highly specialized

prophet, commonly Etruscan. Prophets tended to communicate with the gods

about more distant events in the future. The haruspex did his magic by inspecting the

liver of the sacrificed animal, normally a sheep. After the slave who

had killed the sheep handed its liver to the haruspex, the prophet held it in his

left hand, with his left foot on a stone and his right foot on the

ground , and "read" the liver in a clockwise direction. Haruspices could also be personal advisors--Julius Caesar had one.

Luperci:

these priests ran the Festival of the Lupercalia, when

near-naked young men ran around the City, striking the young women they

met with a goat thong. A fertility rite? A purification ritual?

Ordinary priests:

Their job was

to lead the sacrificial process, initiate the sacrifice, and watch.

Evidently, they weren't expected to know what to do, even the right

form of prayer to offer. Their real role was to represent their

aristocratic class, to show the Roman people that the

aristocratic oligarchy was at the top of the social, political,

and religious orders.

Pontifex, pontifices: Their original function was to

look after Rome's first bridge across the Tiber, the City's most

critical crossing point. From there, the pontifices assumed oversight over

other major "crossing

points," for example those between life and death, or communications between the humans

and the gods.

One of the pontifices' most important authority was control of the calendar,

which determined many aspects of Roman life. They could be powerful

decision-makers, especially in moments of crisis. Less dramatically, they kept the annual record of public events

and gave legal advice on family matters, such as

wills, inheritances, family property, adoptions, and burials.

Prodigy: An event which the

Romans considered "unnatural," such as "rains of blood" or

"monstrous births." Would-be prodigies had to be reported to the Senate for

evaluation and consultation with the priests.

Vestal Virgins: The only female priesthood in Rome, its

six members were chosen in childhood. They lived in a special house next

to the temple of Vesta in the Roman Forum and could ride in a wagon. Their various

rituals connected the fertility of the earth, the safety of the flocks

of animals, and human fertility. They were the guardians of ancient,

ancient talismans, including it was said, sacred objects brought by

Aeneas from Troy.

With special privileges went special responsibilities: if a Virgin let the sacred

fire go out, or was unchaste, she could be buried alive.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Web Resources and Books |

|

|

|

|

|

|

General interest

www.wikipedia.com

www.seindal.dk

www.dmoz.org

www.flickr.com

www.sacred-destinations.com

www.unrv.com

Specialized or advanced

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/

Periods/Roman/home.html

www.livius.org

http://oyc.yale.edu/history-art

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Books |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Beard, Mary, et. al,

Religions of Rome (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1998) 2

vols.

Boatwright,Mary,

Hadrian and the City of Rome

(Princeton UP, 1987)

Fox, Robin Lane,

Pagans and Christians (Knopf, 1986)

Potter, David S., "Roman Religion: Ideas and Actions," in Potter, D.S.

and Mattingly, D.J., Life, Death, and Entertainment in the

Roman Empire

(U of Michigan Press,

1999).

Price, Simon,

The Birth of Classical Europe: A History from Troy

to Augustine (Penguin, 2011)

Stamper, John,

The Architecture of Roman Temples: the Republic

to the Middle Empire

(Cambridge U. Press, 2004)

Biographies of the various rulers of Rome, such as Anthony Barrett, ed.,

Lives of the Caesars (Blackwell, 2008)

|

|

|

|

You may contact me, Nancy Padgett, at

NJPadgett@gmail.com |

|

|

|

|