|

|

|

|

| |

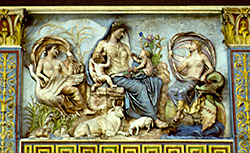

The Tellus panel of

the Ara Pacis, or Peace Altar.

9 BC.

Marble. Museo di Ara Pacis, Rome. A marvelous piece of propaganda

art commissioned by Emperor Augustus.

The altar was originally brightly painted:

Highlights

*

Many Roman wives were perpetually pregnant. Childhood

mortality rates were at least 40%.

*

Childbirth was extremely risky for both mother and child.

*

A family lacking a male heir simply adopted one, even an adult male. Adoption

in ancient Rome was not for the benefit of orphaned children.

*

Roman mothers were in charge of educating their children and instilling

Roman virtues. |

|

Mothers and Children in Ancient Rome

Why get married? The purpose of marriage was to create mothers who could produce children.

Lots of

them: the rate of infant mortality was staggeringly high in the ancient

world -- at least 40%.

A woman, rich or poor, might need to give birth to twelve babies to

ensure three survived past the age of 10.

Young Roman women must have been perpetually pregnant, a high-risk

venture. Many, like

Caesar's daughter Julia, died early deaths in

childbirth.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Childbirth

Women gave birth at home, attended by perhaps a physician,

certainly a midwife, female

relatives, and slaves of the household.

Anesthesia of course was

unknown before the 19th c AD.

Birthing techniques were a blend of science and folk medicine.

The male Greek physician

Soranus, who lived in Rome, was the leading authority on

childbirth.

Women delivered their babies using a birthing chair,

which had a back, arms, and a crescent-shaped hole in the seat, as

pictured on the right. The chair placed the mother in an upright position for

delivery. It was not used for labor.

In earliest Rome, the father had the legal right to keep the newborn or to let it die by exposure. By the time of Julius

Caesar, this custom seems to have died out. |

|

Childbirth in ancient Rome: the

birthing chair and midwife. From Tomb of Scribonia Attice,

Ostia, Italy. Terracotta. 2nd c CE.

Photo courtesy ostia.org

Soranus' treatise

"Gynecology" set out the requirements for the ideal delivery and

recovery rooms, beds, the ideal midwife, and so on. It is also one of

the few surviving works from the ancient world.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adoption

The fly in the ointment: there simply were not enough aristocratic children.

Low fertility of Roman elite males; men away for long periods on

military service; the young wanting a less-encumbered lifestyle? We

don't know why. Caesar, despite his three marriages and numerous

affairs, produced only one legitimate, Roman-citizen child, his

daughter Julia.

Legally, it was difficult for the state

to elevate more families into the aristocracy.

Faced with a low birth rate, the Romans embraced adoption.

Not the kind we have today, to protect children--Roman adoption was aimed at

adults, to promote the interests of the family.

A Roman could "adopt" a male heir who was an adult, even a man who already had

his own family. And even after you the "parent" were dead; just

put it in your will. Caesar

did that. He notified the world

through his will that he

had adopted his nephew Octavian.

Through this legal instrument, he

bequeathed to Octavian

his political mantle as well as financial resources.

Octavian later became the Emperor Augustus.

He tried to increase the number of children by fiat.

|

|

Emperor Augustus/ Octavian. Roman.

Marble bust, National Museum of Rome, Palazzo

Massimo.

Marriage edicts of Augustus:

--Aristocratic wives who had fewer than three children were penalized.

--Women with no children could receive only half of their normal

inheritance. Bachelors had similar penalties.

--Widows and divorced wives under the age of 50 had to remarry quickly

or lose certain legal and social rights.

--Romans of the aristocratic classes greeted Augustus'

fertility rules with a big

"ho-hum", and little obedience.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Educating the children

Roman mothers ruled the household roost.

Once the infant survived the first few years, a Roman mother was responsible for his or

her education. The mother selected the tutor, who provided

home-schooling.

Roman elite male children, and many female children, learned Greek,

Latin, public speaking and a wide variety of other subjects.

She had even more duties: Rome lacked organized social institutions like

churches, public schools, and the like. The good Roman mother was also responsible for instilling the Roman

virtues in her children.

What were these virtues? To be a Roman meant something special and specific: self-control, dignity, respect for the Roman gods, and above all,

loyalty to the family and its ancestors.

The Romans believed these

virtues were needed to maintain the Roman state and society.

Sometimes mature, virtuous heads might be

attached to nubile, sexy-young-goddess bodies. The Romans saw no

contradiction: both fertility and modest

self-restraint were their highest female ideals.

|

|

Funerary stele of the matriarch Vibia

Drosos. Roman. Marble, 2nd c CE. Roman. New York Met.

This Roman mother almost radiates with

Rome's idealized virtues. No dreamy, pale oval face for her. Notice her square face. Her solemn gaze. Her wide

chin. All symbols of the ideal Roman mother: dignified, self-restrained,

modest.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Updated 07-February-2018. You may contact me, Nancy

Padgett, at

NJPadgett@gmail.com |

|

|

|

|

|

|