|

|

Military shield.

Etruscan. Bronze. Gregorian

Etruscan Vatican Museum, Rome.

Etruscans excelled at adorning their shields with a convincingly

ferocious-looking god. It was used to signal to the opponent that the gods

were on the side of the Etruscans. Perhaps the God-On-Shield also served as psychological reinforcement for

themselves. |

|

Etruscan Military and Society

Ancient Italy's tribal warfare

does not leave much for historians to ponder. You can spread out a map

of Italy and track when the peoples of one area crossed over into

another's area. Then set fires to crops and villages and killed or

enslaved whoever they found. That's about it.

The Etruscans, however, were

-more organized

and resource-rich.

-adopted Greek military tactics and weapons.

-then improved on them.

Their outburst of energy lasted several centuries. Bit by bit they conquered others to the north, in

the middle, and

to the south.

|

Etruscan

Society and Violence In addition to

finding joy in extreme luxury, the Etruscans also found it in extreme violence.

Etruscan funeral rites sometimes included human sacrifice of the owners'

slaves. Some slaves had to engage in ritualistic battle

until death. These

may have been the first "gladiators" of the ancient

world.

Etruscan chariot racing drew a ban from the Greek Olympics.

The Etruscan charioteer, unlike the Greek,

was sometimes strapped to his chariot with strong leather belts, with

the reins tied behind his back. The chariot became a virtual

prison for the driver. Racecourses had steep dips, bumpy hills, and

hair-raising

curves; fatal accidents were numerous, and probably expected.

|

|

Chariot racing.

Etruscan. Fresco, wall painting. Tomb in

Tarquinia, Italy. |

|

|

|

|

The Etruscans and Bronze: Military Gear

Many early Italian tribes and communities

fought in only leather

gear. Those who had bronze equipment

gained a considerable comparative advantage

militarily.

The Etruscans controlled the raw material that bronze is made of--copper and tin.

Just as important, the Etruscans were known technically skilled metal workers.

They could turn the raw material into the finished product without

having to depend upon another community.

What followed was a gush of bronze of top quality and significant

quantity.

In addition to bronze helmets, the Etruscans added bronze

protection for the heart area, shields, spears

and daggers, breastplates for the horses, and even musical instruments

for its military musicians.

|

|

Helmet.

Bronze.

Berlin, Altes Museum. To the basic Greek design, the Etruscans added

bronze neck and throat guards.

Modern drawing of a warrior's gear.

Etruscan, 8th c BC. Drawing.

The surviving artifacts are shown in red. Altes Museum, Berlin |

|

|

|

|

This is the

actual bronze

shield pictured in the drawing above.

On the reverse side of the shield are rattles, presumably to scare the

enemy as the warriors approached for combat. |

|

Military

shield, as depicted above in drawing. Etruscan.

8th c BCE. Bronze. Altes Museum (SMB), Berlin |

|

|

|

|

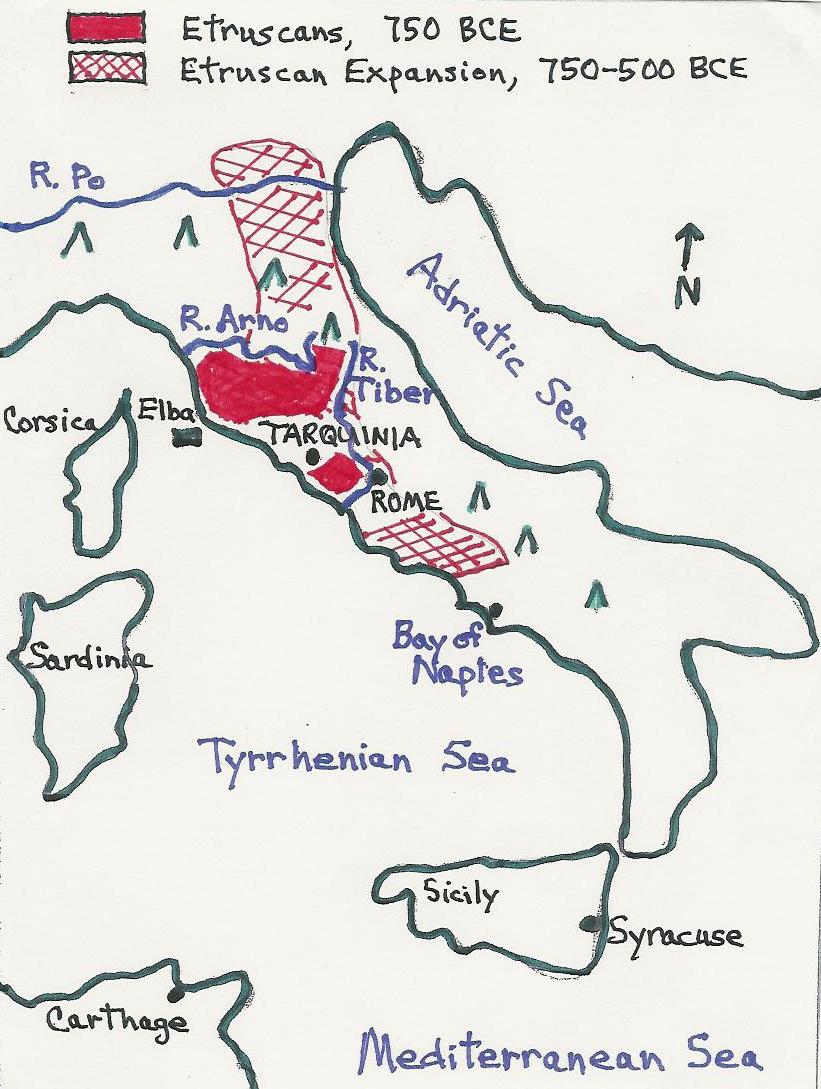

Etruscan Military Tactics

The Etruscans' power base lay between the Arno River (present-day Florence)

and the Tiber (Rome). From there, they expanded for over 250 years.

To the north, they defeated Gallic tribes that had crossed the Alps.

In the middle and south of Italy, they defeated other Italic tribes. At

its high point, over 12 important cities and many smaller communities

were part of the Etruscan polis.

The Etruscans never conquered Rome. |

|

Map of Etruscan expansion to 500 BC |

|

|

|

|

The Etruscans (probably) adopted the

hoplite infantry and its tactical formation, the phalanx,

from the Greeks.

No doubt this was effective, but how this disciplined approach

fused with the more typical "warrior-band-rushes-headlong-forward"

mentality isn't known.

|

|

Etruscan on horseback against Gallic

tribesman.

Tomb. Bologna, Italy. Courtesy Livius.org |

|

|

|

|

Etruscan Sea Power

The Etruscans recognized the control of the Tyrrhenian Sea

was a

must-have to protect their

north-south trade routes. They succeeded with ships equipped with either

single or double banks of oars, and enough manpower to work the oars.

Although the great Athenian naval

invention, the trireme, with its three banks of oars, was known at the

time, it was not adopted. It was probably too expensive. |

|

Etruscan ship.

Tomb fresco.

Tarquinia, Italy. |

| |

|

|

Etruscan

Military Defeat and the End of Etruscan Culture

Little by little, the Etruscans lost ground.

The Gauls attacked from across the Alps, sweeping southward.

Control of the sea went to the Greeks of Syracuse at the Battle of Cumae

in the Bay of Naples in 474 BC.

Etruscan power slipped from this point

on--their trade threatened, coastal

ports vulnerable.

One hundred years later, the Etruscans were much weaker, and in 396 BC, the Etruscans lost on land to the Romans.

The Etruscan city of Veii, only

12 miles from Rome and on the other side of the all-important Tiber, had

battled Rome for over a hundred years. Whoever dominated would control

the river and thus central Italy. The end came when the Roman Army

prevailed in a protracted siege

of Veii.

Even in the darkest hour of Veii, the other numerous Etruscan

city-states would not or could not come to their aid. The Romans

triumphed. Abandoning their usual policy of incorporating the defeated,

they enslaved or slaughtered the people of Veii, looted the enormously

wealthy city dry, and gave their property to Roman citizens.

The sophisticated Greeks had prevailed at sea, and

the upstart and unforgiving Romans on land.

The Etruscans failed to keep what they won. After 250

years of success, Etruscan military power faded slowly away like a specter. |

|

Triumph of Roman

commander Camillus over the (Etruscan) Veii in 396 BC.

Detail. Fresco by Francesco Salviato. 16th c. Florence, Palazzo Vecchio.

Renaissance.

The defeated Etruscans are represented by the

enslaved men in the lower left. Camillus, the Roman general who led the

siege of Veii, is riding in a triumphal

chariot drawn by four white horses. |

|

|

|

| You may

contact me, Nancy Padgett, at

NJPadgett@gmail.com |

|

|

|

|