|

|

The

Sarcophagus of the Spouses.

Etruscan,

550 BC, painted terracotta. Found at Cerveteri, now in the Villa Giulia Museum, Rome. The

Sarcophagus of the Spouses.

Etruscan,

550 BC, painted terracotta. Found at Cerveteri, now in the Villa Giulia Museum, Rome.

A couple happily reposes,

perhaps at a wine banquet

called a "symposium,"

or

perhaps in the afterlife.

This violent Etruscan

society produced beautiful art.

Slideshow of

Etruscan Art in Berlin

Slideshow of

Etruscan Art in U.S. Museums

|

|

The strange world of Etruscan

art, culture,

language, and religion.

The Etruscans

--blissed-out on wine, banquets, exquisite gold jewelry for men and for

women, Greek vases, and tiny

figurines.

--were addicted to brutal, ferocious sports and burial rites.

--cooked up arcane rules for divining the will of the gods.

A culture of extremes, even by the standards of the ancient

world.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Etruscan

Culture:

Antiquity for Beginners

Diving into Etruscan history

is easy, since so little is known about them. We

cannot locate the grave of even a single Etruscan king.

No narrative writings by Etruscans have survived. No histories,

biographies, tell-alls, literature. No poems or racy stories, no

epic adventures. No Homer graced their culture. The Romans eventually

broke away from Greek authors and literature and developed their

own--Horace, for example-- but not the Etruscans. Only inscriptions. The

Etruscan language is truly

a dead language, though not entirely indecipherable.

But if written evidence is puny, the visuals for their culture are not.

The Etruscans were the finest goldsmiths of the

ancient world. Brilliant, intricate designs, carried out by techniques

we still cannot replicate.

Most Etruscan art and artifacts are connected with religion--funerals or

rituals. We modern viewers are subjected to endless numbers of

funerary urns, sarcophagi, tombs and their objects, and the like. The

Etruscans were an unusually "religious" culture, with little separation

between sacred and secular.

|

|

Man on

Horseback.

Etruscan 500 BC, Bronze.

Gregoriano Etrusco Vatican Museum. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Etruscan Art

Etruscan art objects are intense, whether superbly intricate, or simplicity itself.

Their tension vibrates through the air.

Patrons favored expressive, figurative art that looked "natural." To

this naturalism, Etruscan artists added a good deal of abstract design.

Even so, specific individuals remain in the

fog. Nobody "famous" is in evidence.

Look closely at our euphoric pair, the "Happy Spouses". This

sculpture

depicts a type, like an angel in a garden, not identifiable people.

An upturned smile, signifying vitality, was often used, though it was not

unique to the Etruscans.

One point the sculpture underlines: Etruscan wives went out in public.

Wives were considered an integral part of their sophisticated

banquets. The Etruscans' cultural counterpart, the Greeks, kept wives at

home and isolated.

Greek art influenced Etruscan artists, and Etruscans collected Greek

vases by the ton. But soon the Etruscans surpassed the Greeks in

portraiture, jewelry, metalwork, and a sense of motion in their art.

Learn more: Nigel Spivey, Etruscan Art (1997) and Greek Art (1997)

Richard de Puma, Etruscan Art in the Metropolitan Museum (2013)

|

|

The

Sarcophagus of the Spouses.

Etruscan, 550 BC. Painted terracotta. Louvre

Museum, Paris.

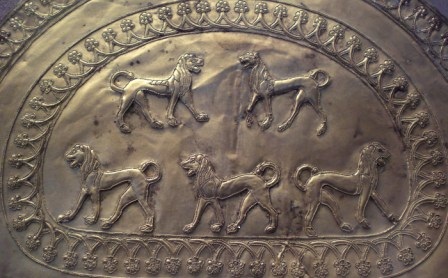

Bracelet.

Etruscan, c 650 BC.

Gold. Gregoriano Etrusco Vatican Museum. Bracelet.

Etruscan, c 650 BC.

Gold. Gregoriano Etrusco Vatican Museum. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Etruscan Good Life: Wearable Art

Vases and tomb frescoes depict a culture

of earthy sensuality. Some Etruscan tomb frescoes would earn an "X"

rating in Hollywood.

Both men and women wore gold, gilded and bejeweled bracelets, armbands,

necklaces, and tiaras.

The artisan would heat the gold and affix it by

the technique of "granulation" into patterns on a gold base.

Unfortunately, since no kilns or goldsmith workshops have been found,

modern archeologists cannot entirely recover these Etruscan techniques.

Women wore earrings and rare and

costly amber, imported from the Baltic Sea communities. The amber was perhaps a

fertility symbol.

Men and women of the wealthy upper classes dressed alike: both donned a long

tebanna, precursor to the Roman toga, and mantles,

with shoes curved upward in points at the toes.

A lush culture indeed--for the wealthy elite.

|

|

Lion

Necklace.

Etruscan, c 650 BC.

Gold. Gregoriano Etrusco Vatican Museum.

Lion

Necklace Detail Lion

Necklace Detail |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Addiction

to Violence

In addition to

finding joy in extreme luxury, the Etruscans also found it in extreme violence.

Etruscan funeral rites sometimes included human sacrifice of the owners'

slaves. Some slaves had to engage in ritualistic battle

until death. These

may have been the first "gladiators" of the ancient

world.

Etruscan chariot racing drew a ban from the Greek Olympics.

The Etruscan charioteer, unlike the Greek,

was sometimes strapped to his chariot with strong leather belts, with

the reins tied behind his back. The chariot became a virtual

prison for the driver. Racecourses had steep dips, bumpy hills, and

hair-raising

curves; fatal accidents were numerous, and probably expected.

|

|

Chariot racing.

Etruscan. Fresco, wall painting. Tomb in

Tarquinia, Italy. Chariot racing.

Etruscan. Fresco, wall painting. Tomb in

Tarquinia, Italy. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

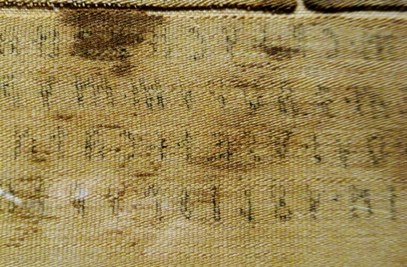

The Etruscan Language

What is it? The Etruscans borrowed the Greek alphabet to

write down their own language but the results look like scratches in the

sand.

What was this language? Mostly we know what it is

not: not Indo-European like Greek or Latin, nor related to Basque,

Hungarian, Finnish, or other orphan languages. Without an

understanding of their language, Etruscan culture is more opaque to us

than are other long-ago cultures.

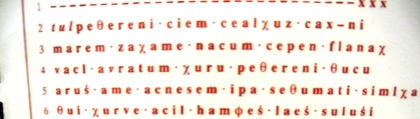

10,000 or so inscriptions have been found in tombs. The "words" or

scratches read right to left, sometimes left to right; sometimes there are no spaces between the

words.

Only a few hundred complete words have been recovered.

Only a few "texts" contain more than 30 lines.

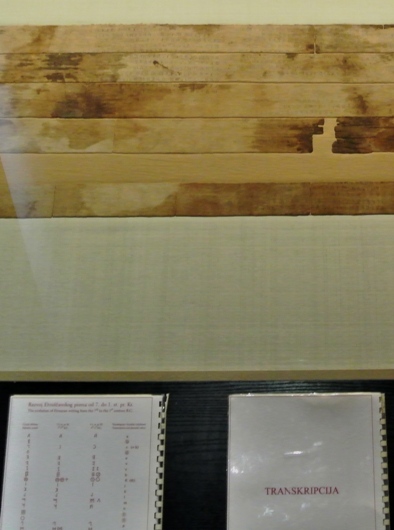

The "Mummy of Zagreb"

linen shroud has the most. It's currently in the National Museum

of Archeology in Zagreb, Croatia. The shroud was

originally a codex book, made of linen. At some point in time, the

folded book was cut into strips to use as a shroud for an Eqyptian

female mummy. Her name was Nesi-Hensu, wife of a

"divine tailor" from Thebes, Paher-Hensu.

The Etruscan letters were written in black ink, and the columns were

makred with a thin line of red ink.

How did an Eqyptian mummy enshrouded in one of the few recorded Etruscan

documents end up in Zagreb, Croatia? In 1848, many Europeans revolted

against the oppressive and authoritarian regimes of their day, much like

the American colonists had done a mere 75 years earlier. But these

Europeans lost, and one of them, a Croatian nobleman named Mihael Barich,

escaped to Eqypt. There he bought the mummy to add to his collection in

Vienna. He gave the mummy to the National Museum of Zagreb in 1859. When

his bequest arrived, other items had been added, including jewellry and

the mummified head of a cat.

Scholars at first thought the writings on the linen were Eqyptian; it

took thirty years to decide they were Etruscan, not Eqyptian.

The Etruscan linen book was restored in the 1980's. It survived the

Balkan Wars of the 1990's and today has a dedicated room in the National

Archeological Museum, Zagreb, Croatia.

National Archeological

Museum, Zagreb, Croatia.

On the way to the

Zagreb Mummy. |

|

Tomb

entry inscription.

Etruscan, 4th c BC, Necropolis of Crocifisso di Tufio, Orvieto, Italy.

Photo courtesy Bill Thayer. Tomb

entry inscription.

Etruscan, 4th c BC, Necropolis of Crocifisso di Tufio, Orvieto, Italy.

Photo courtesy Bill Thayer.

A folded linen codex book on an Etruscan sarcophagus.

Rome, the Vatican Museums.

(1) The Zagreb mummy:

the

Eqyptian female, Nesi-Hensu.

(2) The Etruscan linen book

unfolded (section).

(3)

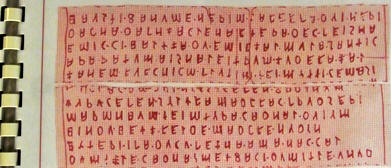

Close-up of the Etruscan letters on the linen above.

(4) Transcription of Etruscan letters above by hand.

.

(4)

Transcription into modern type. From here, scholars are trying to

re-establish the Etruscan language.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Etruscan Religious

Beliefs

Like their art, Etruscan religion was not

personal. Religious inscriptions were rites for avoiding calamity, not a guide for individual spiritual

growth.

Tinia

The god Tinia was the

Etruscan equivalent to Roman Jupiter and Greek Zeus. Although Tinia was the

"supreme" God, to the Etruscans a

personal relationship between an individual and "a supreme God" did not follow.

Etruscan religion was

deterministic. All you could do was find your place in the

pre-determined order of things, by interpreting various signs.

|

|

Tinia.

Etruscan. c 450 BC. Bronze. Getty

Villa.

Tinia is wearing the Etruscan "tebanna." |

|

|

|

|

Many gods

Designating a god as "supreme" did not mean

"exclusive." The Etruscans were an impressive number of gods, with some multi-purpose ones

tossed in.

In the Etruscan world, events occurred because they must have a meaning,

though meaning was discovered through the kind of reasoning we would

find puzzling. E.g., clouds collide in order to release lightning

The Etruscans looked upward to find this meaning: life was governed by gods in the skies.

They obsessed over clouds, lightning, thunder, the position of the

stars, and birds flying over.

|

|

Lasa,

(probably), female divinity.

Etruscan. c 350 BC. Bronze. Getty Villa.

Here Lasa is a tiny, shiny plate holder. |

|

|

|

|

Animal Sacrifice

For important decisions or events, the Etruscan diviner,

called a haruspex if male or nethra if female, would sacrifice

a sheep according to strict rituals. After examining its entrails, the

diviner mapped the surface of its liver to sections of the sky. Perfect

alignment was everything.

Etruscan religious specialists were sought by the Romans for hundreds

of years-- Etruscan religious manuals were still used by the Romans

until the 1st century AD. And in the AD 408, when Rome was under siege

from the Visigoths and its starving inhabitants about to resort to

cannibalism, Etruscan diviners were called in by City officials (and

with the approval of the Christian bishop Innocent I.)

|

|

The Bronze Liver of

Piacenza.

Etruscan. 3rd c BC .Bronze. Municipal Museum of Piacenza.

The Bronze Liver of

Piacenza.

Etruscan. 3rd c BC .Bronze. Municipal Museum of Piacenza.

A sketch of a sheep's liver is mapped

against the regions of the sky. The

Bronze was perhaps

a teaching tool used by Etruscan diviners.

|

|

|

|

|

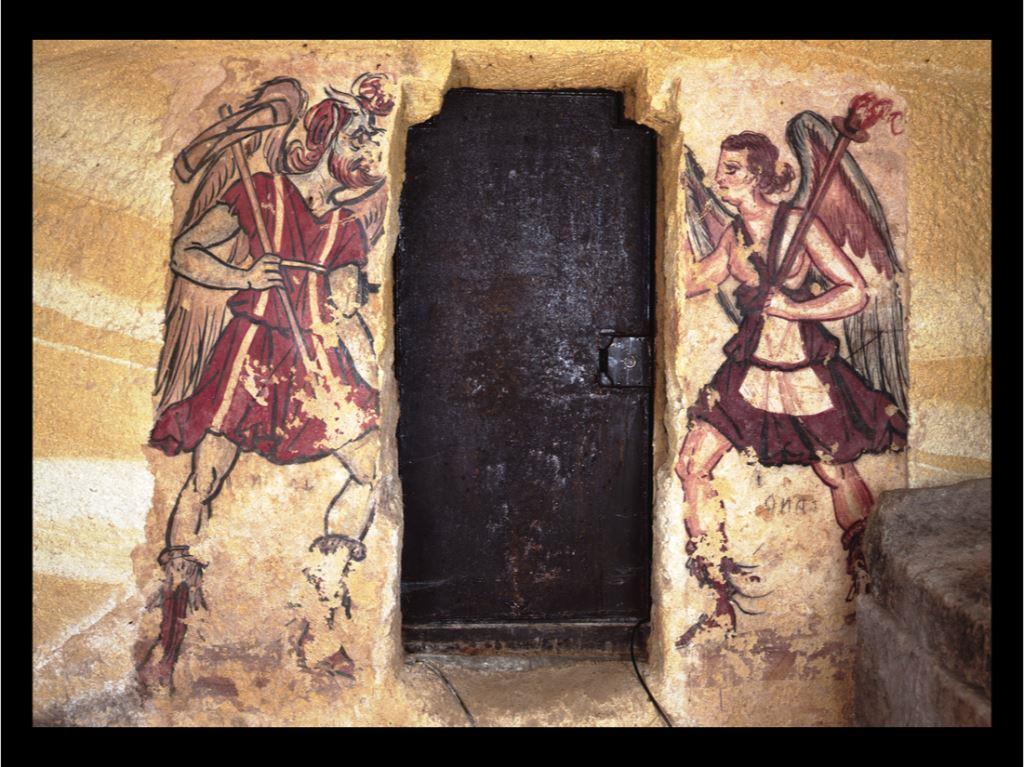

The Etruscan Dead

Burial Rites

The Etruscans seem to have believed literally in a "land of the dead,"

a place, a physical location, for the deceased. The Etruscan dead

were not put into cubbyholes nor buried beneath a tomb-like monument.

They had houses.

How did the deceased get to their afterlife houses? Overland by

horse-drawn chariot, accompanied by spirits. Vanth was one, usually an

attractive female figure. Charu was another, her male partner with a

hooked nose and scowling face.

Where exactly was the chariot headed? Toward a tomb in the earth,

either sunken or inside a mound. The tomb door, sometimes painted, became literally the

entrance to the "land of the dead." Vanth was on the right side,

carrying a torch to help the deceased descend into the dark afterlife,

and Charu, carrying a mallet, stationed on the left.

What would the deceased "see" inside the tomb? A

reconstruction of a complete home, with various rooms. On the walls

might be frescoes of scenes banqueting, games, or dancing.

Bucchero (Etruscan shiny black clay pottery resembling the more

precious 'metal' vases) by the ton-- pouring vessels, plates, and

drinking cups. The Etruscans embraced the drinking party of the

ancient world known as "the symposium," and naturally had the

proper plates and vessels for it, even for the dead.

The insides of a few of the tombs at locations such as Tarquinia show

large-scale painting, the best that has survived until the excavation at

Pompeii. Since we have no evidence of how the Etruscans decorated the

insides of their houses, the tomb paintings might be an acceptable

surrogate, at least for the very wealthy.

For those Etruscan

communities that cremated their dead, the remains

would be placed in terracotta urns. The urns were rarely plain-Jane. Articulated arms, jewelry, wigs, even clothing

were part of the urn's form and decoration. On the lid on the urn might

perch a (stylized) portrait of the deceased. |

|

Etruscan Bucchero (black pottery) vessel.

The Getty Villa, Malibu, CA

Burial urn.

Some Etruscan communities

cremated their dead. Discovered in

Chiusi.

Etruscan. Terracotta. New York Met. Burial urn.

Some Etruscan communities

cremated their dead. Discovered in

Chiusi.

Etruscan. Terracotta. New York Met. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

You may contact me, Nancy Padgett, at

NJPadgett@gmail.com

. Updated

22 July 2016 |

|

|

|

|