|

|

|

|

| |

| |

Mature Woman of the Roman Elite,

Marble Bust, 1st c AD

Flavian Era. Getty Villa

For more on hairstyles:

Glorious Roman Hairstyle Photos

Highlights

* Women of the upper classes could read and write, sometimes Greek as

well as Latin. Unfortunately, almost nothing written by a woman of

ancient Rome has survived. We know of them only through male writers.

* Women outside the elite, even those working in necessary occupations,

were not esteemed.

* Women were portrayed in art as symbols of specific Roman

values--fertility, motherhood, etc.

* The status and role of women changed little over a thousand years of

Roman history.

|

|

Notable Women of Ancient Rome

Notable women were all upper class women: rich,

protected, beautifully adorned. Like males of the upper classes of

Rome, these females were extraordinarily privileged.

How do we know who they were?

This is a big problem: Roman

women have come down to us only through male writers of the ancient

world and beyond. These writers wrote only about the women of the political

elite.

Not surprisingly, Roman women flit in and out of our attention space--a

paragraph here by a Roman historian, a mention there by Cicero in his

letters.

Sometimes there were statues or games or other honors by a husband. A

wife's honors were partly

meant to extol the husband's own virtues, especially if he were in politics.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Notable Women We Wish We Knew More About: |

|

|

|

|

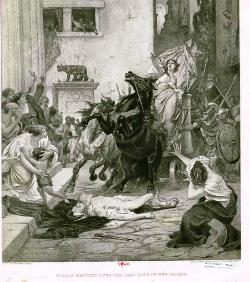

Tullia (legendary), 6th c BC.

Tullia was a

symbol of parricide, the worst of all crimes in

Roman eyes.

Livy the historian tells us that Tullia, the daughter of a very early King of Rome, conspired with her husband to kill her father.

This enabled her husband

to become ruler of Rome.

Tullia then ran over Dad's dead body in her

carriage, underlining the heartlessness of the murder.

Tullia was still

in use as a moral symbol as late as the 19th c. (see photo right).

|

|

Tullia Driving

Over the Dead Body of Her Father,"

by Ernst

Hildebrand, 1889. New York Public Library.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lucretia (legendary),

6th c BC

Lucretia

was Roman virtue personified.

Lucretia has been the subject of myth and literature for centuries, including Rembrandt's

painting and Shakespeare's poem, "The Rape of Lucretia."

Who was

she, this object of so many centuries of attention?

Lucretia

was the wife of a nobleman, and of course beautiful and virtuous.

Although she was in a privileged social position, the

son of the then-King of Rome raped her.

Lucretia extracted from her

father and her husband an oath of vengeance against the

King's

family.

Then she stabbed herself to death.

Why did she, the

victim, kill herself? Roman notions of honor portrayed rape

as dishonoring the husband and the family more

than the woman.

|

|

"Lucretia"

by

Rembrandt van Rijn. Oil. 1664. National Gallery,

Washington, DC. (Photo courtesy National Gallery).

Postscript:

The King's own second-in-command leveraged the event of Lucretia's rape

into a rebellion to overthrow the King.

Traditionally dated 509 BC, the rebellion is the foundation of the Roman Republic.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cornelia, 2nd c BC

Cornelia was the

iconic early Roman mother, wife, and intellectual.

The ancients gobbled up romantic "political reconciliation"

stories and Cornelia's was the best.

Cornelia supposedly sacrificed her own wishes in order to

reconcile two rich, powerful and warring noble families "for the good of

Rome." She did this by marrying a bitter enemy of her father's, T. S.

Gracchus. He was

also 25 years older than she.

Known as "Mother of the Gracchi," Cornelia had twelve children, of whom

three survived infancy.

An early-adopter of Greek culture,

Cornelia was a published writer

whose works, lost to us, were admired in the ancient world. |

|

Cornelia,

mother of the Gracchi. "Cornelia

Presenting Her Children, the Gracchi, as Her

Treasures," Oil. Angelika

Kauffmann, 1785. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Photo Courtesy Va. Museum.

Cornelia is

supposed to have said: "My children are my

jewels."

In fact, Cornelia had an enormous

dowry and enjoyed a lavish lifestyle.

Lavish

apparently was ok as long as it was tasteful. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hortensia, 1st c BC

Hortensia

was the first woman to make a speech in the Roman Forum.

After Julius Caesar's assassination in 44 BC, the new rulers (the Triumvirate sought revenge for

his murder. With money for civil war against the assassins in short

supply, they proposed taxing the property of the 1,400 richest Roman

women.

Hortensia led a delegation of women to Forum, where she declared

that Roman women would enthusiastically help resist a foreign enemy but

would never pay for a civil war.

(Exactly what she said has come down to us in a muddle of fabrication

and speculation).

|

|

Needless to say, Hortensia would not have been invited by the Roman male

political establishment to make a

speech, especially not this speech.

But she prevailed. The

number of women liable to the tax was reduced to 400, and Roman males

who owned property were

now also taxed. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Terentia, Tullia, and Publilia,

1st c BC

These three are the only women known to us from private letters.

They were the wives and daughters of Cicero.

Terentia was his first wife. Tullia was their daughter.

Publilia was his much,

much younger second wife. It was not a match made in heaven. Cicero wrote

extensively to his friends about the

three females in his life.

In addition, there were lots of letters between Cicero and his wives and daughter. Cicero's side of the letters have survived.

|

|

Cicero.

Marble bust. Capitoline Museum, Rome |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Octavia, 1st c BC

Octavia was one of the first Roman

women whose likeness appeared on an official coin.

Octavia was the sister of Octavian, Julius Caesar's nephew and heir,

who became Rome's first

Emperor, (and changed his name to Augustus.) Brother Augustus delivered Octavia's funeral oration,

an unusual honor for a woman, and built the Gate of Octavia, still

standing, in her memory.

Octavia was also the (4th) wife of Mark Anthony. Being by all

accounts a good

person, she took care of Mark Anthony's children by his third wife.

This called for a very big heart indeed, as Mark Anthony then abandoned Octavia for Cleopatra.

Unfortunately, Octavia's great goodness could not prevent

outsized badness in her offspring. Her direct descendants were among the

most horrible of all Roman Emperors--Caligula, Claudius, and Nero. |

|

Octavia. Marble bust. 1st c. Getty Villa.

The poet

Vergil admired Octavia. She reportedly fainted when Vergil read his verses of poetry

to the Emperor.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fulvia,

1st C BC

How Not to Be a "Good

Roman Wife."

Fulvia was Mark Anthony's

first wife, and she represents the aggressive,

independent, political woman of the late Roman

Republic. Although women are now figuring more

prominently in historical accounts, their "appropriate"

role appears not to have changed all that much from

500 years previously.

Fulvia's ultimate

transgression was her foray into a sphere outside

the old role of the Good Roman Wife. Here's how the

story goes, from the male writers of ancient times:

After Julius Caesar's death,

civil war raged between his nephew Octavian/Augustus

and Mark Anthony. Fulvia supposedly appeared before

husband Anthony's troops while Anthony was on

another front. She urged the troops to stand loyal to

him against Octavian. She held councils of war with

Roman senators. She put on a sword. She issued the watchword

to the troops.

|

|

Still, Anthony's troops,

led by his brother, were defeated. And guess what?

Anthony blamed Fulvia for

the rout.

When she lay dying, he did not

visit her.

End of the ancients' version of the story.

We are left wondering: beneath this history, is there another

story?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Livia, 58 BC- AD 29

Loyal and supportive wife, or ruthless plotter and poisoner?

Livia was Emperor Augustus' second wife. She was considered a fine

example of a Roman "matrona."

Livia wore neither excessive jewelry nor

pretentious costumes, took care of the household, and was loyal to

her husband. For thirty years, Livia stayed in the imperial

background, in the shadow of Augustus' sister, Octavia (wife

of Mark Anthony). Augustus dedicated a public statue to Livia.

Livia's villa north of Rome was famous for its beautiful frescoes,

now in Rome at the

National Museum delle Terme,

Palazzo Massimo. (The "House of Livia" on the Palatine Hill was not built by or

for Livia.)

Livia had her own circle of political clients and pushed many protégés

into political offices. She just as energetically pushed others out. Livia

certainly had a hand in the exile of stepdaughter Julia the Elder and

her daughter Julia the Younger.

She tirelessly campaigned for

her son Tiberius, from an earlier marriage, to become Emperor upon Augustus' death.

She succeeded.

The ancient scandal-mongers relish

telling how Emperor Tiberius soon tired of Mom's influence: Tiberius exiled himself

to get away from Livia. He did not even attend

her funeral. |

|

Livia.

Marble Bust (fragment). 1st c. Getty Villa.

Livia was around 60 when this portrait bust was

made, but she wanted to be pictured as youthful.

Livia depicted as Pax, goddess of Peace.

Roman gold coin ("aureus") 36

AD. On the other side of the

coin is her son, the Emperor Tiberius.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Julia the Elder,

39 BC-AD 14

The Wild Child

Julia the Elder was the only child of the

Emperor Augustus. She was witty, smart, kind to people, and beloved,

at least at first, by her father.

But all the major male ancients

considered her the symbol of female profligacy.

Julia had an affair(s?) and partied

wildly with Roman patricians, including the son of Mark Anthony,

Dad's old nemesis.

It's not

too hard to figure out why: on the day of Julia's birth her father divorced

her mother, Scribonia, and took Julia away. When Julia was two, Dad

engaged

her to a political ally's son, though this marriage never took place.

When she was fifteen, Father married her off to her first cousin, Aunt Octavia's

son Marcellus.

Marcellus died only two years later, and she was handed off again to a

man 25 years her elder, Agrippa. By chance, they were quite happy and

had several children.

But husband Agrippa died, and Dad Augustus forced her

too quickly into a 3rd marriage to step-brother Tiberius. At the time,

Tiberius was married to someone else, to whom he was truly attached. The

marriage was a disaster for both Julia and Tiberius, and it ended in

divorce.

For her adultery and "treason," her father exiled

her to a small, uninhabited island. Later he let her return to a town in

the "toe" of Italy.

|

|

Julia, (probably),

daughter of Augustus. 1st c. Marble bust. Altes

Museum, Berlin.

Postscript: Father eventually died.

Julia's ex-husband Tiberius became

Emperor. Tiberius exacted revenge upon poor Julia for the humiliations

he had suffered from her wild affairs: Julia was forced to live in

one room of her house with no human contact.

Julia died soon thereafter.

Tiberius may have starved her to death, or she committed suicide, or both. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sulpicia, 1st c AD Sulpicia is the

only woman whose writings, Latin poetry, have survived.

Sulpicia is thought to have lived during the

reign of the Emperor Augustus. Six of her love poems have survived.

Sulpicia's poems were published with those of a male poet; for centuries

they were thought to be his.

|

|

Scholars now think they

have found other fragments by Roman women poets.

They have found 2 lines by

Sulpicia Caleni, 45 lines by Julia Balbilla on a Colossus in Egypt, and an inscription on a pyramid. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Agrippina the Younger,

1st c AD

She wrote memoirs, now lost, that were admired by Tacitus and Pliny the Elder.

Agrippina is also credited with murdering people, evidently many people, including her

third husband and uncle, the Emperor Claudius. She allegedly presented him with a

plate of poisoned mushrooms at a banquet.

She herself was perhaps murdered by her son the Emperor Nero. Nero had

her assassinated after a very contrived boating accident failed to do so. |

|

Agrippina the

Younger. Marble bust. 1st c AD. Getty

Villa. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Julia Domna, 2nd c AD Well-read, well-educated,

and well-heeled.

Julia accompanied her husband the Emperor

Septimius Severus on his military campaigns, highly unusual for a wife.

His campaigns included England, at that time a scary and wild

place.

Julia was also a serious student of philosophy and a

noted patron of the

Sophist philosophers.

Her son Caracalla was not so wonderful. When his father the Emperor died,

Caracalla promptly murdered his younger brother, Geta, to gain the

throne.

Julia Domna

apparently forgave all, because she accompanied son Caracalla on his

military campaigns.

Julia Domna committed suicide after Emperor Caracalla was assassinated by a

fellow army officer. |

|

Julia Domna.

Marble Bust, 2d c AD. Palatine Museum.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Women of the Late Empire

In the later Empire, the city of Rome and

its old Roman Senatorial political

and social elites lost importance. The Army, rather than the

senators or the sitting emperor might make or break an Emperor.

Usurpers abounded. There sometimes were as many as four

emperors ruling at the same time.

The Emperor's seat moved all over the

map--Trier, Milan, Ravenna, and finally settled on two capitals, one in

Constantinople and the other in the West (Ravenna, Italy).

Many Emperors and other top Imperial officials

were born outside Rome, and some Emperors did not set foot in Italy for

most of their reign. A few were from obscure social origins. The Late

Empire was a fluid mixture of "barbarians"-- those not culturally

Roman-- and the old Roman elites.

The lives of the wives of the late Emperors reflected these changes.

Galla Placidia, 5th c. AD

Many Roman empresses

were children of Roman Emperors

who moved between barbarian and traditional Roman Imperial families.

A good example is Galla Placida. Placidia, involved in Imperial

political life for most of her own life, was the daughter of a Roman

Emperor (Theodosius I) and his wife, herself the daughter of an earlier Roman

Emperor.

Placidia was raised in the household of a "barbarian" Stilicho the

Vandal and his wife, Serena, and engaged to their son. She eventually

married a Visigoth ruler, Ataulf. Ataulf was

assassinated, and she was married off to a traditional Emperor,

Constantius III.

With him, they had a future Emperor of the Western Empire, Valentinian

III.Barbarian women

Barbarian women were considered by the Romans to be strong,

sometimes acting more manly than their mates.

Barbarian marriages were considered very solid.

Barbarians were invariably depicted as

living in cold climates with only a few skins for clothing.

Above all, they lacked

urban settlements and the city's resulting high culture.

Based on a pastoral economy, barbarians ate peculiar food-- dairy

products, meat, bird's eggs, not the grains or olive oil of the Roman

Mediterranean economy. Early Christianity and Roman Women

Some women

found Christian religious institutions, usually a nunnery, a welcome new

option for their lives. More on this topic later...

|

|

Galla Placidia.

Medallion. 5th c AD.

Gold. Bibliotheque National, Paris.

This medallion was struck by

Placidia's brother, the

Emperor Honorius. One of the more

powerful women in Late Imperial politics, Galla

Placidia was a devout Christian.

Barbarian woman

surrendering to Roman conqueror. Roman Coin, called the Arras

Medallion. British Museum, London.

The woman represents barbarian London and the

conqueror is Emperor Constantius.

"Barbarians in

submission" are one of the longest-lasting

conventions in Roman art. |

|

|

|

|

|

Updated 04-August-2015. You may contact me, Nancy Padgett at

NJPadgett@gmail.com |

|

|

|

|

|

|